Case Report

Laparoscopic gastric bypass in patients with unexpected intestinal malrotation:

Report of 2 cases and review of literature

* Joana Patrício,* Ânia Laranjeira,* Arnaldo Machado,* Manuel Carvalho,* Soraia Silva, * Margarida Amaro,*Manuel Bento, * Jorge Caravana

- * Department of General Surgery, Hospital do Espírito Santo, E.P.E, Évora, Portugal

- Submitted: Saturday, December 14, 2019

- Accepted: Sunday, January 12, 2020

- Published: Friday, January 24, 2020

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Background

Intestinal malrotation is a rare congenital abnormality that occurs as a result of an arrest of normal rotation and fixation of the embryonic gut. In adult age, it is extremely difficult to diagnose due to the non-specificity or lack of symptoms and is most commonly found intraoperatively.

Case Presentation

Two bariatric female patients were admitted for surgical treatment after multidisciplinary evaluation. Both of them underwent laparoscopic

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass during which were found to have complete intestinal malrotation, unknown before surgery. None had experienced episodes of intestinal obstruction or other symptoms that suggested intestinal malrotation before. The postoperative period was uneventful and both were discharged on postoperative day 3, after an oesophagogastroduodenal transit that confirmed the diagnosis and excluded any other complication. The result in weight loss was identical to that of patients without anatomical abnormality.

Conclusions

aparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is a bariatric treatment that can be successfully performed in patients with intestinal malrotation without the need of conversion to open operation, even if it is recognised only during surgical intervention. Nevertheless, before transecting the stomach or the intestine, the whole abdominal anatomy of the patient must be carefully explored to identify if modification of the surgical technique is necessary and feasible.

Keywords

Intestinal malrotation, gastric bypass, laparoscopy, obesity.

Introduction

Diagnosis of morbid obesity is increasing nowadays and despite all the innovation in medical approaches most patients only have consistent results with surgery. Laparoscopic

Roux-en-Y bypass is actually the most common procedure performed to treat morbid obesity and has a low rate of mortality [1]. This technique implies a gastrojejunostomy anastomosis to which is indispensable the mobilization of the first part of the jejunum to the upper abdomen. Regardless of the rarity of the abnormal anatomical changes in the intestinal gut, when present they can compromise the usual surgical technique.

Intestinal malrotation occurs when the normal rotation of the embryonic gut is arrested or disturbed during

in utero development. As a result, two anatomic variations develop, Ladd’s bands (fibrous attachments between caecum and posterior peritoneum that may obstruct the duodenum) and narrow mesenteric base, which predispose to symptoms of gastrointestinal obstruction, such as intermittent vomiting or abdominal pain

[2]. Although most frequent in neonates and children, malrotation can be first diagnosed in adults. In adult age, the clinical presentation is variable, and most cases are asymptomatic with malrotation being accidentally discovered by imaging studies obtained for other purposes, during unrelated surgeries or autopsies

[3]. An upper gastrointestinal series is the best examination to visualize the duodenum and therefore the “gold standard” for diagnosing intestinal malrotation in adults. The Ladd’s procedure, consisting of division of Ladd’s bands, widening of the mesentery and incidental appendicectomy, is the standard surgical repair [4].

It is estimated that malrotation occurs in one in 500 patients undergoing

Roux-en-Y bypass [5]. Bariatric surgeons need to be aware of the incidence of malrotation and be prepared to modify their surgical plan accordingly. The authors present two cases of malrotation identified intraoperatively during laparoscopic

Roux-en-Y bypass for obesity treatment that did not compromise the surgical option but evidenced some technical difficulties.

CASE REPORT

Two patients with a 20-year history of obesity were evaluated in a multidisciplinary meeting and decision to operate (laparoscopic

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) was made because of unsuccessful weight control with dietary measures.

Patient 1 was a 45-year-old female, with previous surgical history of an orthopaedic operation and medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and with a body mass index of 40 Kg/m2.

Patient 2 was a 47-year-old female, with a medical history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes and hyperlipidaemia, with a body mass index of 42 Kg/m2.

Both of them had had a complete preoperative assessment, including full history and physical examination, nutritional and psychological evaluation, blood tests (complete blood count, coagulation, liver and renal function tests), chest X-ray, electrocardiogram, abdominal ultrasound, functional respiratory tests and upper endoscopy with Helicobacter pylori testing. All exams were within normal range and none of the patients presented any complaints to abnormal gastrointestinal function, namely vomiting, bloating, diarrhoea or constipation.

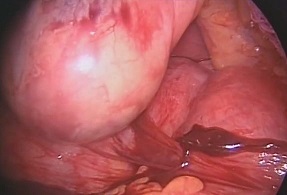

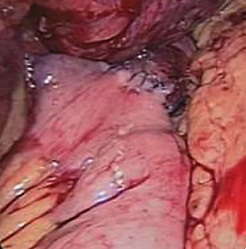

Both surgeries were performed by the same surgeon, and in both cases, intraoperatively, after creating the gastric pouch, an abnormal anatomy was noticed, with a non rotation of the mesentery which included absence of treitz angle, the small intestine occupying the right side of the abdomen and the colon occupying the left, with no transverse colon running across the abdominal cavity, as it usually does, since the entire colon was on the left side and absence of colonic attachments. In both cases, the caecum was on the left iliac fossa and Ladd’s bands were present (Figure

1and 2).

Figure 1: Ladd’s Bands of Patient 1

Figure 2: Ladd’s Bands of Patient 2

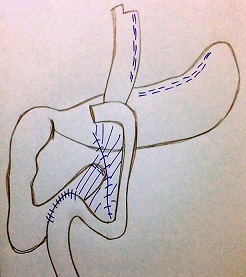

The duodenum and proximal jejunum were inspected. Ladd’s bands were overlying the duodenum and were divided. The jejunum was divided 70 cm distal to the pylorus, and an end-to-side gastrojejunal anastomosis was performed with a 45mm linear stapler oversewn with nonabsorbable over a 45 French bougie (Figure

3). The Roux limb was measured clockwise to a length of 120 cm toward the patient’s left abdomen, keeping the biliopancreatic limb on the patient’s right side of the abdominal cavity. The side-to-side jejunojejunostomy was created with a single 45-mm stapler. All mesenteric defects were closed with running silk sutures. A prophylactic appendectomy was not performed due to the age of the patients and the position of the caecum and appendix in the pelvis. The final result of the operation is pictured in

Figure 4.

Figure 3: Aspect of gastrojejunal anastomosis

Figure 4: Final aspect of the surgery

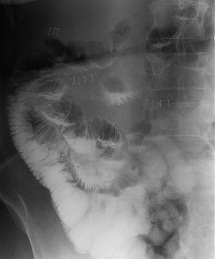

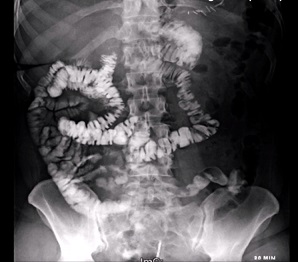

Both patients had an uneventful postoperative course and were

discharged on the third day post op, after a normal oesophagogastroduodenal

transit (Figure 5and 6), tolerating a liquid diet.

Figure 5: Oeso-gastro-duodenal transit of Patient 1 on postoperative day 2

Figure 6: Oeso-gastro-duodenal transit of Patient 2 on postoperative day 2

On one-year follow up, both patients had a good nutritional and psychological status and good quality of life. Patient 1 lost 27 kilos, with a BMI of 30 Kg/m2, corresponding to a percentage of excess weight loss of 56, 5%. Patient 2 lost 43 kilos, with a BMI of 26, 4 Kg/m2, corresponding to a percentage of excess weight loss of 91, 5%

Discussion

Intestinal malrotation occurs in about 1 of 500 live births [6]. In adults it is rare, and the true incidence remains unknown. It is widely agreed that approximately 90% are diagnosed in symptomatic children, the majority in the first 2 weeks of life. The incidence of adult congenital rotational anomalies, noted in contrasted radiographic studies, is around 0, 5% [7].

Malrotation is clinically defined according to the criteria described by Dott: angle of Treitz lying to the right of the superior mesenteric axis, adhesions binding the cecum (or right colon) to the duodenopancreatic block, and inversion of the superior mesenteric vessels at their origin (artery to the right of the vein) [8].

Theoretically, if rotation is arrested at first embryologic stage (between 5th and 10th week), the position of the intestine takes the name of “complete common mesentery” or “non rotation”, with the small intestine occupying the right side of the abdomen and the colon occupying the left side, both connected by a “common mesentery”. In this position, the intestine is not at risk of total small bowel volvulus, because the root of the mesentery is wide, with the first jejunal loop in the right upper quadrant and terminal ileal loop located at a distance in the left iliac fossa. When rotation is arrested at the second embryologic stage (around 10th week), the position of the intestine is termed “incomplete common mesentery” or “incomplete rotation”. In this case, the duodenojejunal junction lies to the right of the superior mesenteric artery and the cecum is located in the subhepatic region above the origin of the superior mesenteric artery

[9]. At the same time, the mesentery of the proximal jejunum is bound to the mesentery of the terminal ileal loop, the so-called “Pellerin’s mesenteric fusion”[10]. This form of malrotation carries a higher risk of total small bowel volvulus because the root of the short mesentery, centred on the superior mesenteric artery, forms a narrow pedicle with both proximal and distal limbs of the loop in close proximity. In practice, midgut malrotation results in a spectrum of abnormal mesenteric base lengths with subsequently variable risks for midgut volvulus, with or without Ladd’s bands [11].

There are only a few reports of intestinal malrotation diagnosed during bariatric procedures and these are limited to clinical case reports, with most patients being asymptomatic

[12]. Even when symptomatic, malrotation is usually associated with malabsorption and weight loss due to intermittent vomiting, so it is unlikely to make that diagnosis in an obese patient. This illustrates the rarity of this abnormality. Bariatric surgeons need to be aware of this anatomical variation and identify it as soon as possible, as it implies a tailored surgical approach

[5]. The most important thing is to identify the malrotation before dividing the stomach or the small bowel. So, the golden rule in performing a laparoscopic gastric bypass is to clearly visualize the duodenojejunal angle right from the beginning of the operation, allowing unknown bowel malrotations to be identified. This will let the surgeon take special care with jejunal mobilization (that can be harder) and not doing antiperistaltic anastomosis or extremely distal anastomosis. If a common mesentery is present, the gastric bypass is performed in the same way but in order to avoid an antiperistaltic anastomosis, all the anastomosis should be done “in mirror” to the usual technique, meaning the biliary-pancreatic loop comes from the patient’s right (on the left on the screen) and the alimentary loop comes from the patient’s left (on the right of the screen). All mesentery defects must be closed to prevent internal herniation

[12].

It is consensual that, when identified, Ladd’s bands should be divided but no intestinal or mesenteric plication procedures have been proved to be useful or even safe and the bowel should be left as it is without fixation

[12]. Appendicectomy is not mandatory in this setting, especially if the appendix lies in the normal pelvic position and the patient is not adolescent. However, one must be aware that an atypical appendicitis might occur with pain in other location besides the right iliac fossa [11].

For asymptomatic adult patients diagnosed with malrotation by imaging studies alone, the choice between operative corrections versus continued watchful waiting is controversial [13]. While some authorities advocate close observation in those with minimal (eg, acid reflux) or no symptoms, the majority of experts favour operative correction with a Ladd’s procedure in such patients due to the potential risk of bowel ischemia. On the other hand, all the cases identified intraoperatively should undergo surgical correction, particularly if the patient has a history of chronic gastrointestinal complaints [14]. Although it does not return bowel to a normal configuration, since it is anatomically impossible, the Ladd’s procedure minimizes future risk of volvulus by widening the base of the mesentery and placing the bowel in a position of nonrotation.

Following a Ladd’s procedure, the risk of acute volvulus still persists but is much lower

[15]. It is important to explain to patients that in the presence of any acute abdominal symptoms they should promptly seek medical attention and an emergency upper gastrointestinal series or a CT scan should be done to rule out acute volvulus or other complications.

The increase of obesity with the consequent increase in laparoscopic bariatric procedures raises the question about including some new test to rule out a malrotation abnormality before surgery, such as the oesophagogastrojejunal transit that is already part of pre-operative assessment in some centres. This allows patients to know their condition before surgery and give their informed consent for a concomitant surgical correction. Their justification is that oesophagogastrojejunal transit is a non-invasive and low-cost test that identifies the most aberrant forms of malrotation which would eventually need a more different approach. In most centres, the ultrasound

is done routinely to investigate gallstones but it is extremely hard to identify malrotation, especially in obese patients because of the amount of fat tissue [12].

Routine CT imaging is not required before bariatric surgery to look for these uncommon anomalies. However, if the patient does have an abnormal rotation, it is worthwhile to do a CT scan to determine which type to help plan the operation [11].

Conclusion

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as an obesity treatment can be successfully performed in patients with intestinal malrotation without the need of conversion, even if it is recognised only during surgical intervention [11]. Nevertheless, technical aspects of the procedure are different from an individual with normal anatomy (such as the orientation of the Roux limb), so before transecting the stomach or the intestine, the whole abdominal anatomy of the patient must be carefully explored.

In conclusion, in the setting of the incidental finding of asymptomatic intestinal malrotation during laparoscopic bariatric surgery, combined Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and Ladd’s procedure can be conducted successfully [16]. The results in weight loss seem to be similar to that of patients with normal anatomy. Insufficient evidence exists concerning the relative risk of complications with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with normal bowel anatomy versus intestinal malrotation

[7].

Learning Points

- Intestinal malrotation is rare and may be asymptomatic until adulthood.

- There are only a few cases reported as an intraoperative finding during bariatric procedures.

- Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass can be successfully performed in patients with intestinal malrotation but some technical aspects should be taken into account in order to prevent complications.

Authors' Contributions

All people who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing or revision of the manuscript.

JP: conception, design and composition of the manuscript guided by the actual data and evidence; critical revision of the article.

AL: participate on patient’s surgery; important contribution to the critical revision of the article; approved the final version to be published.

AM: participate on patient’s surgery; important contribution to the critical revision of the article; approved the final version to be published.

SS: participate on patient’s surgery; important contribution to the critical revision of the article; approved the final version to be published.

MC: Responsible for patient’s surgery, outcome and follow-up; important contribution to the critical revision of the article; approved the final version to be published.

MA: Responsible for patient’s surgery, outcome and follow-up; important contribution to the critical revision of the article; approved the final version to be published.

MB: Important part of clinical and treatment judgement by multidisciplinary evaluation; made a critical revision of the article and approved the final version to be published.

JC: Important part of clinical and treatment judgement by multidisciplinary evaluation; made a critical revision of the article and approved the final version to be published.

Ethical Considerations

A written consent was obtained from the patient. Copy of

consent is available with authors

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Funding

None

Acknowledgements

None

References

[1]. Gagné D., Dovec E., Urbandt J. Malrotation-an unexpected finding at laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a video case report. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011 Sep-Oct; 7(5):661-3. [PubMed]

[2]. Durkin ET,. Lund DP., Shaaban AF, et al. Age-related differences in diagnosis and morbidity of intestinal malrotation. J Am Coll Surg 2008 Jun; 206(6):1249. PMID: 18387471 .[PubMed]

[3]. Pickhardt PJ, Bhalla S., Intestinal malrotation in adolescents and adults: spectrum of clinical and imaging features. Am J Roentgenol. 2002 Dec; 179(6):1429-35. PMID: 12438031.[PubMed]

[Full Text]

[4]. Kotobi H., Tan V., Lefèvre J., Duramé F., Audry G., Parc Y. Total midgut volvulus in adults with intestinal malrotation. Report of eleven patients. J Visc Surg. 2017 Jun; 154(3):175-183. PMID: 27888039.[PubMed]

[5]. Aviv Ben-Meir., Indukumar M., Mark

G., Karen S. Laparoscopic Roux-en-y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) in patients with

malrotation. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 2009; 5(3), P29. [Full

Text]

[6] James A., Zarnegar R., Aoki H., Campos G. Laparoscopic gastric bypass with intestinal malrotation. Obes Surg. 2007 Aug; 17(8):1119-22. PMID: 17953249 [PubMed]

[7]. Cross B., Bhalla V., Warren J. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the setting of congenital malrotation: a report and review of the literature. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013 Nov-Dec; 9(6):e91-5. PMID: 23562381.[PubMed]

[8] Dott NM. Anomalies of intestinal rotation: their embryologyand surgical aspects with reports of five cases. Br J Surg. 1923; 251–286. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800114207.

[Full

Text]

[9] Ladd WE. Congenital obstruction of the

duodenum in children. N Engl J Med 1932; 206:277—83 [Full

Text]

[10]. Peycelon M., Kotobi H. Complications des anomalies embryologiques de la rotation intestinale: prise en charge chez l’adulte. EMC Techniques Chirurgicales - Appareil Digestif 2012; 7:1.

[11] Prathanvanich P., Chand B. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in a known case of midgut nonrotation with literature review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014 Jul-Aug; 10(4):747-54.[PubMed]

[12]. Radwan K., Pierre B., François V., Christophe B., Patrice L. Gastric bypass with unknown intestinal malrotation: Required attitude. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2013; 4 (12): 1134-1137. PMID: 24291678.[PubMed]

[13] Malek MM., Burd RS. The optimal management of malrotation diagnosed after infancy: a decision analysis. Am J Surg. 2006 Jan; 191(1):45-51. PMID: 16399105 .[PubMed]

[14]. Gallarín S., Espin J., Moreno P., Salas M. Unusual intestinal malrotation in an adult. Cir Esp. 2016 Jan; 94(1):e21-3. PMID: 25649333.[PubMed]

[15] Buchmilleer T. Intestinal malrotations in adults. UpToDate. 2017 Jul

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/intestinal-malrotation-in-adults [Last

Accessed February 12, 2020]

[16] Haque S., Koren JP. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in patients with congenital malrotation. Obes Surg. 2006 Sep; 16(9):1252-5. PMID: 16989715 [PubMed]