Case Report

Utilization of a Nasal Trumpet for Successful Drainage of a Biliary Cystadenoma to Eliminate the Possibility of Leakage

1 Joshua A Schammel,2 Christine MG Schammel, PhD 2David P Schammel, MD 3Steven D Trocha, MD

- 1University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Greenville, Greenville SC, USA

- 2Department of Pathology, Pathology Associates, Greenville SC, USA

- 3Academic Department of Surgery, Prisma Health Upstate, Greenville SC, USA

- Submitted Wednesday, May 8, 2019;

- Acceptedriday, May 24, 2019;

- Published Tuesday, June 4, 2019

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Introduction:

Biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas are rare cystic neoplasms that represent <5% of all hepatobiliary cystic masses and are extremely difficult to differentiate by non-invasive modalities. Aspiration of these cysts to alleviate patient symptomology and obtain a definitive diagnosis is suggested; however, due to the possibility of seeding during drainage, and with metastatic potential, aspiration is discouraged and surgical resection is recommended.

Case Presentation:

The patient presented with a possible biliary cystadenoma through inconclusive imaging. The centrally located mass obstructed visualization of the hepatic vasculature eliminating the possibility of en bloc resection. A nasal trumpet was surgically adhered to the surface and drainage was accomplished through the lumen of the trumpet. There was no possibility of leakage, allowing for mass removal.

Conclusion:

This innovative surgical resection of a centrally located biliary cystadenoma that obstructed visualization of the hepatic vasculature and created a difficult and potentially dangerous procedure, avoided any seeding and leaking, resulting in successful surgical removal of the biliary cystadenoma.

Keywords:

drainage of large abdominal cyst, resection

Introduction

Biliary cystadenomas (BCA) and cystadenocarcinomas (BCAC) are rare cystic neoplasms that represent less than five percent of all hepatobiliary cystic masses [1]. These lesions arise most often in the liver and, with less frequency, in the bile ducts [1]. BCA is most often associated with asymptomatic middle-aged women (90%), and, thus, diagnosis is often incidental [2] however, diffuse abdominal pain may occur. While BCA are benign and do not pose direct harm to the patient, they possess the ability to undergo malignant transformation and thus, have the potential to recur and metastasize [1]. While BCA are easily differentiated from simple cysts due to the multiloculated nature and presence of septae within the cyst as determined by ultrasound, CT, or MRI, precise identification of BCA by imaging has proven to be difficult [3]. Image guided aspiration of suspected BCA has been suggested [4] however, due to potential malignancy and possibility of seeding during drainage [4], this is not considered a viable option. In fact, fenestration, aspiration, sclerosis, internal drainage, marsupialization or partial resection with or without cavity ablation has been shown to result in high recurrence rates (80-90%), thus, complete surgical resection is considered the standard of care [5].Here we report a case of BCA in which a novel surgical technique was used to drain the cyst in a manner that eliminates the possibility of dissemination and resulted in appropriate surgical removal.

Technical Case Report

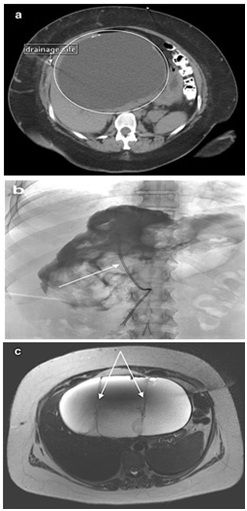

The patient is a 30-year-old white female (BMI of 46.7) with a medical history of a cholecystectomy, ulcers, dysphagia, GERD, diabetes insipidus, and multiple removals of simple liver cysts. She presented to another facility with nausea and abdominal pain. CT imaging revealed a cyst of the left hepatic lobe of her liver segment 3/4b within the proximity of the biliary tree. The cyst was found to be approximately 30 cm in size and was aspirated at an outside facility. Cytology revealed a serous cyst with bilious fluid. The patient was referred. At our facility, imaging was reviewed. A 22.4 cm x 15.7 cm cyst was identified on the CT as was evidenced by the presence of the pigtail catheter used for decompression. Contrast was seen in the biliary tree and thus, ablation was contraindicated (Figures 1a). Image-guided aspiration was ordered to relieve symptoms and to exclude the possibility of communication with the biliary tree. CT guided aspiration was completed and approximately 4 liters of green fluid were obtained. Fluoroscopy indicated the complex nature of the cyst and, due to apparent obstruction, could not rule-out biliary tree communication ((Figures 1b) . Ethanol ablation was not performed due to the inclusion of BCAC in the differential. Surgical resection was advised. Pre-surgical MRI noted a 21 cm x 21 cm x 12 cm mass with extrahepatobiliary septations with an obscured biliary tree, ruling out a simple cyst (Figures 1c).

Figure 1: Imaging of the cyst.a) Biliary Cyst on CT: Referral CT scan illustrating the cyst (circled) and the drainage site b) Fluoroscopy: Note the pigtail catheter. With contrast, communication with the biliary tree could not be ruled out, retaining biliary cystadenoma in the differential, a contraindication for ethanol ablation. c) MRI of the biliary cyst: Noted are the thickened septae ruling out a simple cyst.

At operation, the cyst was found to be 15 cm x 20 cm and encompassed the entire midline and right upper quadrant of the liver. The cyst possessed a tense nature that made it impossible for the surgeon to safely reach the hilar structures or the hepatic veins and, thus, no consideration was made for en bloc resection. At this juncture, a sterile evacuation of the cyst was performed. Specifically, a nasal trumpet was surgically superglued to the surface of the cyst (Figures 2). Suction was percutaneously placed in the nasal trumpet, completely collapsing the cyst and removing 3.8 liters of biliary fluid without spillage (Figures 3). The suction tube and trumpet were carefully removed and the contact site was over-sewn with purse-string to prevent any other leakage. Following the procedure, the hilar structure and the right side of the liver were visible. An intraoperative ultrasound of the liver was performed to determine the absence of further cystic structures. A left hepatectomy, segments 2, 3, and 4, was completed for complete sac resection.

Figure 2: Sealed attachment of the nasal trumpet to the BCA. Intraoperative view with dome of the cyst obscuring any view of the hilum or hepatic veins. Nasal trumpet is demonstrated secured to the dome of the cyst.

Figure 3: Sealed drainage of the BCA. Decompressed cyst with the view of normal liver parenchyma near the nasal trumpet with visualization of the hepatic veins.

The patient tolerated the surgery well and was discharged home a week post-oprerative. The final pathology report identified the cyst to be a papillary mucinous biliary cystadenoma. In addition, fibrosis was noted in the hepatic parenchyma as well as bile duct proliferation consistent with large duct obstruction.

Discussion

While BCA is benign, malignant transformation of these lesions to BCAC has been reported to be as high as 20% [6], necessitating extreme care in management. Preoperative imaging, through ultrasound, CT and MRI, while differentiating BCA from simple cysts, has a diagnostic accuracy as low as 30%, warranting a high level of suspicion [7] when BCAC is in the differential. Preoperative core needle biopsy to detect malignancy is not recommended due to limited accuracy and the risk of seeding and dissemination [7]. Thus, complete resection upon the suspicion of BCA/BCAC is warranted [5].

While most BCA arise from the intrahepatic biliary system [1] and range from 1.5 cm to 35 cm [8], the location of the cyst within the liver determines the appropriate surgical intervention [8]. Formal resection can be a reasonable option for peripheral lesions; however, enucleation may be the only option for centrally located lesions involving central vascular or biliary structures [3]. In this case, the mass was relatively large and obscured the primary hepatic vascular structures, making resection and enucleation difficult and dangerous, if not impossible. The only option was to drain the cyst so that the essential anatomic structures could be appropriately visualized for the resection.

All procedures currently in use for draining cysts have the possibility of leakage, and as such portend morbidity. Leakage in removal of teratomas, noted in greater than 13% of cases, can cause peritonitis leading to resultant adhesion formation and bowel dysfunction [9]. In the management of other gynecologic cysts where histology is uncertain, particularly ovarian cysts, ultrasound or CT-guided aspiration cannot be recommended as it might lead to dissemination of malignant cells [10]. Similar issues are seen in the management of giant hydatid cysts [11, 12]. In fact, many authors agree that, while there are various innovations in the form of suction devices to enable controlled suction of contents with minimal spillage, these devices may not be easily available and are very often ineffective [12].

In the liver, management of simple cysts includes laparoscopic deroofing and alcohol sclerotherapy; however, management of other cysts is more complex [13] and diagnostic uncertainty should result in surgical resection to assure a neoplastic condition, such as cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma, is not allowed to persist [14]. When surgical resection is not an option, as in the case presented here, other procedures must be used. In this case, as critical structures were obscured by the cyst, aspiration prior to resection was the only option. In considering means for aspiration, many procedures and products claim to successfully minimize the possibility of cyst content leakage with ‘leak proof lids’; however, they reduce, but don’t eliminate, the possibility of leakage, particularly at the site of puncture. This is unacceptable in the setting of a potentially malignant lesion. Thus, the need for the described procedure.

The nasal trumpet was a perfect implement to assist in the drainage as the flat end of the trumpet, once superglued to the cyst, creates a seal that, when the cyst is punctured through the trumpet, would not allow cystic fluids to leak into the belly. An environment in which the cyst could be safely drained to facilitate complete surgical resection was then created. As noted, once the cyst had been drained, the trumpet was removed and the attachment site was securely sutured to prevent any leakage of remaining fluid. This allowed for removal of the cyst from the sterile field without any spillage, thus completely eliminating the possibility of seeding.

Given the uncertainty in pre-operative diagnosis of BCA and the possibility of BCAC, all potential BCA should be treated as if they were malignant, with safety protocols in place to avoid seeding the belly with the potentially malignant cystic fluids. Based on the location of the cyst, or when complications arise during the resections of these cysts, it is necessary to develop innovative mechanisms to assure optimal patient outcomes. We report the use of a nasal trumpet providing a successful, cost-effective and safe alternative when such surgical difficulties arise in resection of these lesions.

Learning Points

1)Biliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas are rare cystic neoplasms that should be differentiated prior to surgical removal; if this is not possible, complete en bloc surgical removal is essential.

2)Enucleation may be the only option for centrally located lesions involving vascular or biliary structures, or in situations where critical structures cannot be appropriately visualized; it is essential that leakage be completely prevented to avoid seeding of the peritoneal cavity.

3)Many procedures claim to successfully minimize the possibility of cyst content leakage andmany of the suction devices are equipped with ‘leak proof lids’; however, these don’t eliminate the possibility of leakage at the site of puncture which is unacceptable in the setting of a potentially malignant lesion.

4)All potential BCA should be treated as if they were malignant, with safety protocols in place to avoid seeding the belly with the potentially malignant cystic fluids.

5)The nasal trumpet was a perfect implement to assist in the drainage as the flat end of the trumpet, once superglued to the cyst, creates a seal that, when the cyst is punctured through the trumpet, would not allow cystic fluids to leak into the belly.

Competing Interests

All authors report no conflicting financial or non-financial interests.

Authors Contributions

Joshua Schammel is the primary author, did all literature searches, procured all case report information (details, figures), prepared a draft of the manuscript

Christine Schammel is the primary editor and facilitated procurement of information and editing of the manuscript; responsible for all formatting

David Schammel is the pathologist that diagnosed the patient specimen, participated in editing the final manuscript

Steven Trocha is the surgeon and primary care provider for the patient, he identified the case, pioneered the technique and assisted in procurement of all information and figures, and participated in manuscript development and editing.

Patient Consent

Patient was consented upon consenting to receive care at our institution under a universal consent. This consent was verified by IRB approval at our institution Pro00066448 which was approved prior to initiation of the report and completed 2/23/2018 at 10:43am EST.

References

[1].Arnaoutakis D, Yuhree K, Pulitano C, Zaydfudim V,Squires MH, Kooby D, Groeschl R, Alexandrescu S, Bauer TW, Bloomston M, Soares K, Marques H, Gamblin TC, Popescu I, Adams R, Nagorney D, Barroso E, Maithel SK, Crawford M, Sandroussi C, Marsh W, Pawlik TM. Management of Biliary Cystic Tumors: A Multi-institutional Analysis of a Rare Liver Tumor. Annals of Surgery 2015; 261: 361-7.[PubMed] [PMC Full Text]

[2].Chen Y, Li C, Liu Z, Dong J, Zhang W, Jiang K. Surgical management of biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma of the liver. Genetics and Molecular Research 2014; 13: 6383-90.[Pubmed]

[3].oares KC, Arnaoutakis DJ, Kamel I, Anders R, Adams RB, Bauer TW, Pawlik TM. Cystic neoplasms of the liver: biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2014; 218:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.08.014.[PubMed] [PMC Full Text]

[4].Baba H, Belhamidi M, Fahssi M, Ghanmi J, Zentar A. The management of a cystic hepatic lesion ruptured in the bile ducts: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2017;11: 1-5.[PubMed][PMC Full Text]

[5].Ahanatha Pillai S, Velayutham V, Perumal S, Ulagendra Perumal S, Lakshmanan A, Ramaswami S, Ramasamy R, Sathyanesan J, Palaniappan R. Biliary cystadenomas: a case for complete resection. HPB Surg 2012:501705. doi: 10.1155/2012/501705.[Pubmed][PMC Full Text]

[6].Vyas S, Markar S, Ezzat T, Rodruiguez-Justo M, Webster G, Imber C, Malago M. Hepato-biliary cystadenoma with intraductal extension: unusual cause of obstructive jaundice. J Gastrointest Cancer 2012;43:32–37. doi: 10.1007/s12029-011-9289-6.[PubMed]

[7].Emre A, Serin K, Ozden I, Tekant Y, et al. Intrahepatic biliary cystic neoplasms: Surgical results of 9 patients and literature review. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2011; 17: 361-5.[PubMed] [PMC Full Text]

[8].Sang X, Sun Y, Mao Y, Yang Z, Lu X, Yang H, Xu H, Zhong S, Huang J. Hepatobiliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas: a report of 33 cases. Liver Int 2011;31:1337–1344. doi: 10.111/j.1478-3231.2011.02560.x.[PubMed]

[9].Shamshirsaz A, Shamshirsaz A, Vibhakar J, Broadwell C, Van Voorhis B. Laparoscopic Management of Chemical Peritonitis Caused by Dermoid Cyst Spillage. Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons 2011; 15: 403-5.[PubMed] [PMC Full Text]

[10].Eltabbakh G. Laparoscopic Surgery for Large Ovarian Cysts-Review. Trends Gynecol Oncol 2016;2:109https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/laparoscopic-surgery-for-large-ovarian-cysts-review-.php?aid=83535.

[11].Hemmati SH. How to build a simple and safe laparoscopic hydatid evaluation system JSLS. 2014;18: pii: e2014.00314. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00314.[PubMed] [PMC Full Text]

[12].Acharya H, Agrawal V, Tiwari A, Sharma D. Single-incision trocar-less endoscopic management of giant liver hydatid cyst in children. J Minim Access Surg 2018; 14:30–133. doi:10.4103/jmas.JMAS_42_17.[Pubmed] [PMC Full Text]

[13].Maruyama Y, Okuda K, Ogata T, Yasunaga M, Ishikawa H, Hirakawa Y, Fukuyo K, Horiuchi H, Nakashima O, Kinoshita H. Perioperative Challenges and Surgical Treatment of Large Simple, and Infectious Liver Cyst - A 12-Year Experience. PLoS One 2013; 8: e76537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076537.[PubMed] [PMC Full text]

[14].Macutkiewicz C1, Plastow R, Chrispijn M, Filobbos R, Ammori BA, Sherlock DJ, Drenth JP, O'Reilly DA. Complications arising in simple and polycystic liver cysts. World J Hepatol 2012; 4: 406–411.doi:10.4254/wjh.v4.i12.406.[pubMed] [PMC Full Text]