Case Report

Anal canal gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) – A rare primary location

Ânia Laranjeira, Joana Patrício, Rogério Senhorinho, Jorge Caravana

Hospital Espírito Santo E.P.E. Largo Senhor da Pobreza 7000, Évora, Portugal

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background

A gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) is a mesenchymal neoplasm that can arise in any part of the digestive tract. Anorectal location represents 5 to 10% of all GISTs and nearly 2 to 8% of anorectal GISTs arise from the anal canal.

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old woman was referred to our Institution due to a perianal mass that was growing in the last two years. A pelvic MRI documented a large mass in the intersphincteric space of well-defined limits with central necrosis. A local excision was undertaken while preserving sphincter function, since the mass showed well circumscribed limits without invasion. The histological diagnosis of high-risk GIST was made. The patient completed 3 years of adjuvant chemotherapy with Imatinib and has had 5 years of follow-up without local recurrence or distant metastases.

Conclusions

The objectives of sphincter preservation and optimal quality of life must be weighed against the risks that are associated with the highly variable recurrence behaviour of anorectal GISTs.

Keywords

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour, anal canal, KIT gene

Introduction

The gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) represents 1% of all gastrointestinal malignancies. [1-5] GIST of the anal canal is extremely rare and there is no widely accepted treatment approach for this neoplasia. Although surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment, it is still uncertain whether local or radical excision should be appropriate for anal canal GIST. The authors present a case of perianal high-risk GIST that was managed by local excision.

Case Report

A 75-year-old woman was referred to our Institution due to a perianal mass that was growing in the last two years with associated proctalgia. The patient denied other local symptoms, bleeding, tenesmus, bowel habits changes, weight loss, anorexia or asthenia. Due to social reasons, she had not sought medical care. The patient’s medical history included anaemia by iron deficiency and she had no past of surgery or significant personal or family history of cancer. At the rectal exam, there was a large mass in the perianal left side starting from the anal verge. It was a non-tender mass which was encapsulated, well-defined, immobile and had approximately 5 cm in its greater dimension. This lesion contacted with the internal sphincter and then extended distally into the perianal left side. No blood, purulent content or mucus was observed. No lymph nodes were palpable. At the proctoscopic evaluation the lesion presented as an indurated mass without invasion of the anal canal. A punch biopsy was suggestive of a mesenchymal tumour. Routine blood test revealed anaemia (haemoglobin 9.2 g/dL).

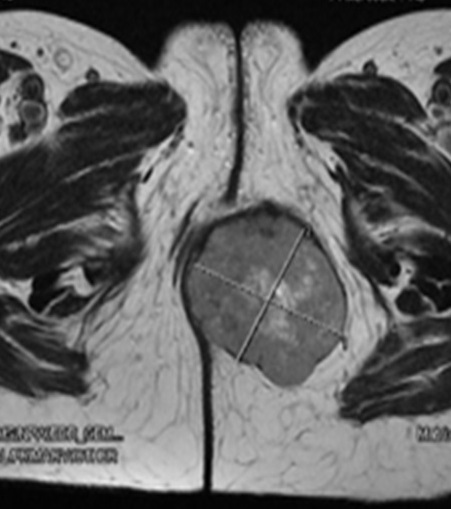

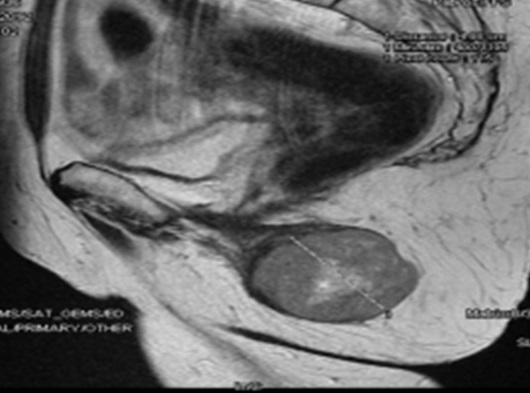

A pelvic MRI (Figure 1 and

2) documented a large mass (5.2 x 6 x 5 cm) of the perineum in the intersphincteric space of well-defined limits, with central necrosis and irregular thick walls. This mass contacted the internal sphincter of the anal canal and the emergence of the vagina and vulva without invading them, and pushed the surrounding structures without destruction. There was no documented lymphadenopathy. Total body CT scan did not show any lymph node enlargement in the proximity or distant metastases.

Figure 1: Pelvic MRI (Axial) showing a large well defined

mass in the perineum (5.2x6x5) with central necrosis and thick wall.

Figure 2: Pelvic MRI (Sagittal section) showing the mass in

contact with the internal sphincter of the anal canal, vagina and vulva without

any invasion.

The patient underwent local excision under regional anaesthesia. The perianal incision was made over the palpable lesion. Since the mass was easily seen, capsulated, non-infiltrating the surrounding structures and had well defined limits without invasion of sphincter’s fibres it was possible to perform a complete surgical resection (R0) while preserving sphincter function and optimal quality of life. The local excision was carried out, resecting just a small amount of fibres of the anal sphincter. The histopathological examination revealed a fibrous-elastic mass of 7 x 5.5 x 5.5 cm with haemorrhagic areas and necrosis, with high mitotic index (7/10 HPF). The specimen margins were clear (R0). The histological diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumour of high risk (G2) was made. The immunohistochemical examination was positive for CD34, CD117 and vimentin. Mutational analysis of the KIT gene was positive for p.E554_V559del mutation in exon 11 of the KIT gene. Postoperative course was uneventful. No implications on anal continence were observed and the patient was discharged only on postoperative day 4 to allow better wound care. The patient completed 3 years of adjuvant chemotherapy with Imatinib, 400 mg daily. Currently, the patient has had 5 years of follow-up without clinical or imaging evidence of local recurrence, locoregional or distant metastases. Follow-up with clinical history, physical examination, digital rectal exam and abdominopelvic CT scan has been performed every 3 to 6 months for the first 5 years and from now on it will be done annually.

Discussion

Most GISTs arise from the stomach (60%), followed by the small intestine (30%), colon and rectum (5-10%) and oesophagus (5%) [1,

2]. In the large bowel, GISTs are more common at the rectum. Anorectal location represents 5 to 10% of all GISTs and nearly 2 to 8% of anorectal GISTs originate in the anal canal [6,

7].

GISTs varies in size from a few millimetres to large tumours; the median size at presentation is about 5 cm [2,

3]. The biologic behaviour of a GIST is variable but it is becoming clear that with long follow-up, all GISTs have the potential for malignant behaviour, even those with 2 cm or less [3,

5].

GISTs are commonly associated with nonspecific symptoms. Bleeding from mucosal ulceration is the most common symptom of gastric, bowel and anorectum GISTs. Other symptoms of a GIST are site specific. Anorectal GISTs can present with bleeding, pain, mass sensation, constipation, and anaemia and may be diagnosed as a palpable mass by rectal digital exam or haematochezia [2,

5].

Abdominal/pelvic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) is the preferred method to diagnose the location and extent of all GISTs and helps in assessing resectability, staging workup, surveillance and follow-up [1,

3]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be the imaging modality for GISTs at specific sites, such as the rectum or the liver [5]. Endoscopy is used in selected cases of primary gastric mass. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can show some features that may suggest a malignant behaviour of the GIST and allows for a EUS-directed fine-needle biopsy (EUS-FNAB) [2,

5]. In the case of an anorectal GIST beyond a complete clinical history and physical examination with digital rectal exam, it should be performed an endoscopy, pelvic imaging such as EUS or MRI, and a staging CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. The central cystic or low-attenuation areas by CT or the central hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging by MRI are distinctive aspects of a GIST, when compared to a carcinoma [5]. Preoperative biopsy may cause bleeding and may increase the risk of tumour spillage, since these tumours are usually soft and friable. Biopsy is not required if the tumour is technically resectable and any neoadjuvant therapy is recommended. After removal of a suspected GIST, postoperative pathology assessment is essential to confirm the diagnosis. Instead, biopsy is performed when there is indication for neoadjuvant Imatinib or in the case of metastatic or unresectable disease [1,

3, 4].

GISTs do not have a specific staging system. Clinicopathological studies of GISTs (Miettinen et al, Lasota J et al., at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology [3,

8-11]) have identified that the most important prognostic factors are size, mitotic index and location. These large series classify the recurrence risk based on a long-term follow-up. Considering size, GISTs ≤2 cm can be considered as essentially benign, but lesions >2 cm have a risk of recurrence [3]. For GISTs of equal size, rectum is a more aggressive location, followed by the small bowel and then gastric tumours [3,

4]. Furthermore, tumours with high mitotic activity may recur and metastasize even if they’re smaller than 2 cm [4]. There’s no specifically data for anal GISTs and they overlap the significant prognostic factors of all GISTs. GISTs larger than 5 cm or with more than 5 mitoses/50 high power fields (HPF) behave aggressively, whereas size 2 to 5 cm with mitotic index less than 5/50 HPF have an intermediate risk profile [5,

7].

There are a few series of anorectal GISTs which show a local recurrence (LR) rate of 75% in tumours >5 cm, despite its mitotic rate, and of 62% in tumours <5 cm, but with ≥5 mitoses/50 HPF [5,

11, 12]. Thus, anorectal region is associated with a poor prognosis.

The pathological diagnosis depends on the morphology and immunophenotype of these tumours [4]. KIT proto-oncogene (CD117) is the immunohistochemical marker of GISTs in about 95% of cases [1-4]. GISTs harbour gain of function mutations leading to a constitutive activation of the tyrosine kinase receptor. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) – Imatinib Mesylate – is the therapy of choice and approximately 80% of GISTs respond to Imatinib [1]. The mutated exons in the c-KIT gene has prognostic value and predict sensitivity to the therapy [1,

3, 4]. In a series of 133 anorectal GISTs including 3 cases of anal origin, the tumours were CD117 positive in 96%. Exons 9, 11 and 13 of the c-KIT gene were amplified in 29 cases [7].

This case report has the particularity of an extremely rare location of a GIST which manifests as a perianal mass. Due to its primary location and patient complaints, the clinical diagnosis was possible by physical examination as the mass was easily seen on the perianal left side and by rectal digital exam as the mass contacted the internal sphincter of the anal canal. Presumptive diagnostic imaging and exclusion of metastatic disease with no intention of neoadjuvant therapy allowed the decision of surgical treatment as the primary approach.

For primary resectable GISTs, surgery is the mainstay of treatment and the goal is to achieve negative histological margins (R0) with an intact pseudocapsule and an acceptable risk of morbidity [3,

4]. Lymphadenectomy is usually not performed because lymph node metastases are rare on GISTs [1,

3, 4]. Neoadjuvant Imatinib is recommended for large tumours with extensive organ involvement and meanly positioned. In these cases that are considered unresectable or marginally resectable downsizing the tumour may alter the type of surgery and reduce the need for more extensive resections [1,

4]. Primary GISTs usually displace and do not infiltrate adjacent structures, so extensive multi-visceral resections are rarely indicated, it should instead be accompanied by minimal consequences on patient’s morbidity. Anorectal GISTs should be approached by a sphincter-sparing approach [4].

A local resection was performed in our patient without increasing morbidity and sparing most fibres of the internal anal sphincter. The controversy of this case relies on the type of surgery since there isn’t enough evidence about the long-term prognosis for anal canal GISTs. A primary approach by local excision has a lower morbidity, preserves a good function of the sphincter and is relatively safe in low-risk tumours but is not being known data of the probability of recurrence. A radical approach as abdominoperineal resection (APR) would undoubtedly have a major effect on quality of life and could offer a better oncological cure, but it is not known to have a reducing value in recurrence rate.

To this date, treatment guidelines defined by National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend that a primary surgical approach should include resection with the aim of obtaining clear margins (R0) always avoiding major functional consequences for the patient [4,

13]. The aims of sphincter preservation and optimal quality of life must be weighed against the risks from the highly variable recurrence behaviour of anorectal GISTs. Data of recurrence after complete surgical resection has been reported from retrospective case series [5] and it seems to be higher in cases of local resection against radical resection, but the type of resection had no effect at the incidence of metastasis and the overall survival.

A high estimated risk of recurrence includes tumours <5 cm in size with high mitotic rate (>5/50 HPF), tumour rupture, or a risk of recurrence greater than 50% after surgery [4].

Giuseppe et al, [6] recommended an initial local excision to define the risk of aggressive behaviour and the resection margins and thereafter proceed to a more aggressive treatment, if the GIST belongs to high or very high risk group.

A retrospective study [14] concluded that GISTs >5 cm or with a mitotic index >5/50 HPF regardless of size, were considered highly malignant with high recurrence rate or metastases after surgery (55 to 85%). They recommended a more aggressive surgical approach to reduce LR, although it cannot be correlated with overall survival.

Miettinen et al, [15] concluded that the recurrence or metastatic patterns of anorectal GISTs are similar to other GISTs. It is not rare a long course of disease and recurrence several years after resection of primary tumour. Series reporting a high rate of LR have a longer follow-up [5,

16]. A collective surgical series of GISTs from all locations [17] revealed no effect of margins on overall survival, reflecting the equally distant metastasis rate in cases of R0 resections. Hassan

et al., [18] found that one third of recurrences are both local and distant and occur within 2 years, carrying a higher rate of LR in high-risk GISTs.

A multidisciplinary review of these cases should be always performed to complete the staging, consider whether more radical surgery is required, determine if adjuvant therapy is needed and to ensure long-term follow-up [5].

Despite the scarce evidence concerning the optimal management of the high-risk perianal GIST, our patient was treated by a lesser radical surgery based on the patient’s age and status performance. This decision was made after the multidisciplinary review of the case and with the agreement of the counseled patient and family. The goal was a curative treatment with lesser morbidity and no evident disadvantage on the overall survival, against a potential risk of LR.

The use of adjuvant Imatinib after resection of a primary GIST is the standard treatment for patients at intermediate and high risk of recurrence

[1, 4]. Two of the largest trials of adjuvant Imatinib for completely resected GISTs by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG Z9000 and Z9001) included only a few patients with anorectal GIST, so data for the anal subgroup are scarce [7].

The NCCN guidelines of 2013 recommend follow-up with abdominal-pelvic CT or MRI every 3 to 6 months during the first 5 years and then annually for intermediate and high risk patients [4].

Conclusions

Approximately 2 to 8% of anorectal GISTs arise in the anal canal. Size, mitotic index and location dictate the type of resection.

The objectives of sphincter preservation and optimal quality of life must be weighed against the risks that are associated with the highly variable recurrence behaviour of anorectal GISTs.

However, the method of resection did not significantly affect the development of metastasis or survival, as the number of metastases and deaths were similar with both surgical methods.

Learning points

Anal canal GIST represent only 3% of all anorectal mesenchymal tumours. [6]

Local excision has the advantage of minimal morbidity and sphincter preservation, while radical excision may offer a better oncological cure.

Long-term follow-up is necessary for these patients as recurrences may develop many years after the initial surgery.

Author’s contributions

All people who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing or revision of the manuscript.

AL: responsible for patient’s investigation, outcome and follow-up; participation on patient’s surgery; conception, design and composition of the manuscript guided by the actual data and evidence; critical revision.

RS: responsible for patient’s investigation, diagnosis, patient’s surgery, outcome and follow-up, data analysis, interpretation and also for doing the critical revision of the article; approved the final version to be published.

JP: important contributions to the conception and design of the manuscript, drafting the article and doing critical revision; approved the final version to be published.

JC: important part of clinical and treatment judgment by multidisciplinary evaluation, made critical revision of the article and approved the final version to be published.

Ethical Considerations

The written informed consent was taken from the patient for publication of this case report.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of Interests.

Funding

None

Acknowledgement

None

References

[1] Hrabe JE, Cullen JJ. Management of small bowel tumors. In: Cameron JL, Cameron AM, eds. Current Surgical Therapy. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011; 106–109.

[2] Gupta P, Tewari M, Shukla HS. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Surgical Oncology 2008; 17; 129-138. PMID: 18234489

[PubMed]

[3] Demetri GD, Benjamin R, Blanke CD,

Blay JY, Casali P, Choi H, et al; NCCN GIST Task Force. NCCN Task Force report:

optimal management of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor

(GIST)--expansion and update of NCCN clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr

Canc Netw. 2007; 5 (suppl. 2): S1-S29 [Free

Full Text]

[4] NCCN Guidelines Version 1. 2013 Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST)

[5] Peralta EA. Rare Anorectal Neoplasms: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor, Carcinoid, and Lymphoma. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2009; 22(2): 107-114. PMID: 20436835 PMCID: PMC2780247

[PubMed] [PMC

Full Text]

[6] Nigri GR, Dente M, Valabrega S,

Aurello P, D'Angelo F, Montrone G, Ercolani G and Ramacciato G. Gastrointestinal

stromal tumor of the anal canal: an unusual presentation. World J Surg Oncol.

2007 Feb 16;5:20 PMID: 17306018 PMCID: PMC1821025 [PubMed] [PMC

Full text] [Free

full text]

[7] Roy A, Wattchow D, Astill D, Singh S; Pendlebury S; Gormly K, Segelov E. Uncommon Anal Neoplasms. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2017 Jan;26(1):143-161. PMID: 27889033

[PubMed]

[8] Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin Diagn Pathol 2006; 23:70-83. PMID: 17193820

[PubMed]

[9] Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29:52–68. PMID: 15613856

[PubMed]

[10] Miettinen M, Makhlouf H, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the jejunum and ileum: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 906 cases before imatinib with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 2006; 30:477–489. PMID: 16625094

[PubMed]

[11] Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors—definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Arch 2001; 438:1–12. PMID: 11213830

[PubMed]

[12] Tworek JA, Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Greenson JK, Appelman HD. Stromal tumors of the anorectum: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999 Aug; 23(8):946-54. PMID: 10435565

[PubMed]

[13] Casali PG, Blay JY, Bertuzzi A, Bielack S, Bjerkehagen B, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bruzzi P, Dei Tos AP, Dileo P, Eriksson M, Fedenko A, Ferrari A, Ferrari S, Gelderblom H, Grimer R, Gronchi A, Haas R, Hall KS, Hohenberger P, Issels R, Joensuu H, Judson I, Le Cesne A, Litière S, Martin-Broto J, Merimsky O, Montemurro M, Morosi C, Picci P, Ray-Coquard I, Reichardt P, Rutkowski P, Schlemmer M, Stacchiotti S, Torri V, Trama A, Van Coevorden F, Van der Graaf W, Vanel D, Wardelmann E, ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014 Sep;25 Suppl 3:iii21-6. PMID: 25210085 DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdu255

[PubMed] [Free

Full text]

[14] Li JC, Ng SS, Lo AW, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Leung KL. Outcome of radical excision of anorectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Hong Kong Chinese patients. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jan-Feb;26(1):33-5. PMID: 17401234

[PubMed]

[15] Miettinen M, Furlong M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Burke A, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, intramural leiomyomas, and leiomyosarcomas in the rectum and anus: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 144 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001 Sep;25(9):1121-33. PMID: 11688571

[PubMed]

[16] Changchien CR, Wu MC, Tasi WS, Tang R, Chiang JM, Chen JS, Huang SF, Wang JY, Yeh CY. Evaluation of prognosis for malignant rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumor by clinical parameters and immunohistochemical staining. Dis Colon Rectum 2004, 47:1922-1929. PMID: 15622586

[PubMed]

[17] DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumours: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000; 231(1):51-58. PMID: 10636102 PMCID: PMC1420965

[PubMed] [PMC

Full text]

[18] Hassan I, You YN, Dozois EJ, Shayyan R, Smyrk TC, Okuno SH, Donohue JH. Clinical, pathologic, and immunohistochemical characteristics of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the colon and rectum: implications for surgical management and adjuvant therapies. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006 May;49(5):609-15. PMID: 16552495

[PubMed]