Case Report

Takayasu’s Arteritis Presenting as Hypertensive Encephalopathy

*Anup Singh, *Sandesh, * Raykar, * Manish Gupta,

- * Department of General Medicine, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, India

- Submitted: Thursday, November 9, 2017

- Accepted: Tuesday, January 23, 2018

- Published: Saturday, January 27, 2018

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Introduction

Takayasu’s arteritis (TA), a form of vasculitis of unknown etiology affects the aorta and its main branches and present with varied clinical presentation. Hypertensive encephalopathy as an initial clinical presentation of Takayasu’s arteritis is a rare manifestation.

Case report

We present a case of 20 year female patient presenting with fever and altered sensorium, with asymmetrical upper limb blood pressure. She was suspected of having arterial occlusive disease and on investigation was found to have narrowing of aorta and its branches suggestive of type V Takayasu’s arteritis. We present this case on account of rare presentation of takayasu’s arteritis as hypertensive encephalopathy.

Conclusion

Takayasu’s arteritis can present with varies features. A high clinical suspicion, prompt diagnosis and treatment along with managing complication associated with it can help in decreasing the mortality and morbidity associated with this vasculitis.

Key words

arteritis; vasculitis; vascular disease; autoimmune; hypertension; encephalopathy

Introduction

Takayasu’s arteritis (TA), a form of vasculitis of unknown etiology, commonly known as pulseless disease or occlusive thromboaortopathy, chiefly affects the aorta and its main branches. It occurs commonly in young women, of less than 40 years of age. Most cases are reported from China, Japan, India and South East Asia. The sign and symptoms of TA are manifestations of vascular insufficiency (due to stenosis, aneurysm or occlusion) and systemic inflammation. Common symptoms include headache, visual symptoms, fever, malaise, weight loss, etc. Usual signs include hypertension, asymmetric pulses and bruit over large vessels. Hypertensive encephalopathy as a complication of Reno vascular hypertension is a rare manifestation of the disease.

Case report

A 20 year female, resident of North Bihar, India presented to us with fever for 3 days duration with altered sensorium. Fever was mild grade and was associated with generalized body ache and mild headache. Her altered sensorium was in the form of decreased responsiveness to commands. There was no history of seizures prior to altered sensorium. Her past, developmental and family history was not contributory. On the day of admission her GCS score was 8/15 (E2V2M4), she was afebrile, pulse 96/min in right radial artery with weak pulse in left brachial and radial artery, all peripheral pulses were present, blood pressure in right upper limb was 210/140 mmHg and left upper limb 140/100 mmHg in supine position. Fundus examination revealed papilledema in bilateral eyes. On auscultation, a bruit was heard over the left carotid artery. Rest of the cardiovascular examination did not reveal any abnormality.

Neck rigidity and kernig sign were absent, plantar response was extensor without any focal neurological deficits. Respiratory system and abdominal examination did not reveal any abnormality. On routine investigation, her hemoglobin was 12.5mg/dl, total leucocyte count was 15,100/mm3 (N87,L10,M2,E1), and platelet count was 1.9lakhs. Her serum creatinine and urea level was 1.4mg/dL and 26 mg/dL respectively with normal electrolyte levels, liver function, Urine routine and microscopy. There was no malarial parasite seen on peripheral blood smear, and antigen card test for malaria was negative. However, her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 76mm/hr and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 44 mg/dl.(Normal reference values for ESR is 20 mm 1st hour for females and 30 mm 1st hour for males, for CRP normal reference value is <6mg/dl). Based on difference in blood pressure in upper limbs with raised acute phase reactants, diagnosis of vasoocclusive disease probably vasculitis was made.

The chief differential kept was; Takayasu’s arteritis with hypertensive encephalopathy, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) with co-arctictation of aorta, Tubercular meningitis with tubercular aortoarteritis, and malignant hypertension. CSF was normal which rules out non specific viral encephalitis and tubercular menungitis. MRI brain was essentially normal which rules out ADEM.

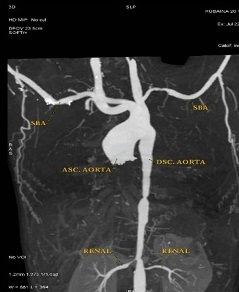

Computerized tomography(CT) angiography of thorax was done which revealed features in favour of Type V Takayasu Aortoarteritis with diffuse circumferential intima media thickness with mild luminal narrowing involving descending thoracic and abdominal aorta and its branches(celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery& bilateral renal arteries. Main pulmonary artery measured 2.0 cm, right pulmonary artery 1.3 cm, left pulmonary artery 1.5 cm, left subclavian artery 5.0mm, and left common carotid artery was 9.0mm. Bilateral renal arteries osteal narrowing was seen with right and left artery measured 2.2mm and 2.6mm respectively.. Short segment aortic stenosis (5.0 mm) was also seen at the level of Diaphragm ((Figure 1&2a-e)).

MRI Brain and MR angiography revealed no abnormality. Colour Doppler of bilateral carotids were normal. Patient was treated with nifedipine (0.3mg/kg/dose, 6 hourly) and propranolol (0.5mg/kg/dose, 6 hourly). Antiepileptic intravenous valproic acid (10mg/kg/day) was given prophylactically and intravenous mannitol (20%) was given to reduce intracranial pressure and other conservative management was given. Patient blood pressure was controlled and she regained consciousness within 3 days of admission. Patient was started on steroids and was discharged on request to be referred to higher centre.

Figure 1: Contrast Enhanced CT Scan showing Left subclavian, Descending aorta & Bilateral Renal artery stenosis.

Figure 2 Contrast Enchanced CT Scan showing A): Arrow showing descending aorta stenosis . B): Arrow showing Left Subclavian artery stenosis C): Arrow showing Bilateral Renal artery stenosis. D): Arrow showing Celiac artery stenosis E): Arrow showing Superior mesenteric artery stenosis

Discussion

Takayasu’s arteritis, a form of vasculitis of unknown etiology, chiefly affects the aorta and its main branches. Patients during the acute inflammatory phase, present with fever, malaise, weight loss, arthralgia, night sweats and in late chronic phase as reno vascular hypertension and its complications. The most common sites of lesions in TA are the aorta (65%) and the left subclavian arteries (93%) [1]. Most common type encountered in India is Type III [2] . Type V TA is extensive involvement of entire aorta and its branches. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) for clinical purpose has developed criteria to differentiate TA with other forms of vasculitis from another [3,4]. Other cause of large vessel vasculitis includes Giant cell arteriris (GCA) which is indistinguishable by histopathology but it occurs mostly in more than 50years of age with external carotid artery with its branches being commonly involved. But around 30% of GCA can involve aorta and its branches.

In TA, hypertension develops in more than half of patients, due to renal artery stenosis, narrowing of aorta and its branches. Neurological manifestations have been found in 52.7% of patients, in which headache was the most common symptom [5]. Other symptoms are visual disturbances and light headedness. Major neurological complications occurring due to hypertension are TIA, cerebral infarction, hypertensive encephalopathy and paraplegia. Some patients present with seizures but is a rare manifestation, usually associated with Progressive reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Neurological complications are related to the combination of carotid and vertebral artery involvement and complications of hypertension and thromboembolic phenomenon. CT angiography (Angio) of thorax was preferred over MRI angiography because it has a better spatial resolution and shorter imaging time than MR angio. Whereas the imaging time with MR Angiography, utilizing free breathing respiratory gated sequences, is 5 to 15 mins, this duration is few seconds with CT angio. MR angio is preferred and has better diagnostic accuracy when trying to assess vessels with heavily calcified plaques and when suspecting anomalous vessels. Since our patient was young, we didn't suspect a pathology involving severe calcification of vessels. Also the widespread systemic manifestations go against vascular malformation. The cost of CT angio is also lower than MR angio. However, CT Angio of cerebral vessels was not preferred over MR Angio in our case because we had to rule out viral encephalitis as well. So MR angio was done in the same setting. MRI is superior to CT in detecting parenchymal changes and brain edema [6,7].

FDG-PET has a good sensitivity for detecting active inflammation in TA where the uptake of ligand is typically seen as a homogenous linear pattern. This highlights an area of increased metabolic activity. Despite its usefulness, there is a lack of standardisation for quantification of ligand uptake.Another issue is the high cost and availability. However, if a patient is caught early in the disease, i.e in stage 1, where significant stenotic changes have not yet occurred, PET can serve as a useful adjunct. Once stenosis has set in the changes will appear on CT angio. Now, it is well known that there are no definite serological markers for TA. The monitoring of a patient, thus, relies on clinical evaluation and ESR and CRP. Many a times ESR and CRP remain normal despite active disease. In those cases PET scan may also be useful for monitoring active disease activity.

Medical management is mainly by corticosteroids, initially started with 0.5 to 1 mg/kg which is continued for 4 to 12 weeks and tapered gradually. Patients who relapse after tapering of steroid can be treated with methotrexate, initially 0.3mg/kg which can be given up to 15mg/kg and gradually increased to maximum of 25mg/week [8]. Small studies and series suggest that other corticosteroid sparing drugs include azathioprine (2 mg/kg per day) or mycophenolate mofetil (2000 mg/day) may be used [9,10]. Other agents like tocilizumab, anti-TNF agents and cyclophosphamide has also shown improvement in small studies and their effectiveness need to be evaluated in large clinical trials [11,12]. In late and symptomatic cases, reperfusion therapy by percutaneous transluminal angioplasty or bypass grafts may be considered [13]. The indications for surgical interventions include uncontrolled hypertension secondary to significant renal artery stenosis, severe symptomatic coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease, stenotic lesions resulting in critical limb ischemia, severe aortic regurgitation, and aneurysms at risk of rupture. Renal angioplasty is more suitable than primary stenting in young patients due to technical difficulty of small access vessels and due to the nature of disease involving long segments, often in an irregular manner and thus predisposing to restenosis. Stenting is more suitable in cases of short focal lesions in the absence of active disease. Therefore, it seems logical to first control disease activity medically before stenting or surgical intervention. Studies have shown that whereas 77.3% patients developed restenosis after angioplasty procedures, only 33% patients who underwent surgical bypass developed restenosis. Thus it might be concluded that surgical procedures have a better long term survival compared to stenting [14] Thus it might be concluded that surgical procedures have a better long term survival compared to stenting.

Prognosis of Takayasu’s arteritis (TA) is a chronic disease whose activity based of inflammatory process intensity. Short term prognosis is favourable but when complications occur due to ongoing vascular involvement the prognosis gets worse. One study investigating prognostic factors associated with this disease found two major predictors of outcome. The presence of active progressive disease and complications like Takayasu retinopathy, aortic regurgitation, hypertension and aneurysm has been found as two strong predictors of making prognosis worse [15]. The 15-year survival in patients with and without a major complication was 66 and 96 percent, respectively, and in patients with progressive disease it was 68 and 93 percent respectively. The prognosis becomes much worse if both, presence of a major complication and progressive course are present with 15-year survival being only 43 percent. These predictive markers of prognosis will help identify patient requiring aggressive treatment.

Conclusion

Takayasu’s arteritis can present with varies features. Vasculitic syndromes are difficult to diagnose and delineate individually as there are no specific biomarkers for certain diseases such as Takayasu areteritis and Giant cell arteritis. The clinical presentation varies with extent of involvement and end organ disfunction. Further, most of vasculitic syndromes share a histopathologic picture. The criteria by ACR have high sensitivity and specificity to differentiate TA from other causes of vasculitis. So, a high clinical suspicion, prompt diagnosis and treatment along with managing complication associated with it can help in decreasing the mortality and morbidity associated with this vasculitis

Authors’ Contributions

AK: literature search and final editing of the draft manuscript.

SR: participated in editing the final manuscript.

MG: prepared the draft manuscript.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Ethical Consideration

The written informed consent was taken from the patient for publication of this case report, The copy of consent is available with the author.

Funding

None

Acknowledgement

None

References:

[1].Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Giordano J,

Leavitt RY, Fauci AS, Rottem M, Hoffman GS.: Takyasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med

1994; 120:919-29. [PubMed]

[2].Sharma BK, Sagar S, Singh AP, Suri S. Takayasu arteritis in India. Heart Vessels Suppl. 1992;7:37–43. PMID: 1360969 [PubMed]

[3].Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder

GG, Calabrese LH, Edworthy SM, Fauci AS, Leavitt RY, Lie JT, Lightfoot RW Jr, et

al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of

Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33:1129-34. [PubMed]

[4].Ishikawa K. Diagnostic approach and proposed criteria for the clinical diagnosis of Takayasu's arteriopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988; 12:964-72. [PubMed]

[Full

text]

[5].Ioannides MA, Eftychiou C, Georgiou

GM, Nicolaides E. Takayasu arteritis presenting as epileptic seizures: a case

report and brief review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2009 Apr;29(6):703–5. [PubMed]

[6].Yamada I, Numano F, Suzuki S. Takayasu

arteritis: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology 1993; 188:89-94. [PubMed]

[7].Yamada I, Nakagawa T, Himeno Y, et al.

Takayasu arteritis: evaluation of the thoracic aorta with CT angiography.

Radiology 1998; 209:103-9. [PubMed]

[8].Hoffman GS, Leavitt RY, Kerr GS,

Rottem M, Sneller MC, Fauci AS. Treatment of glucocorticoid-resistant or

relapsing Takayasu arteritis with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 1994; 37:578-82.

[PubMed]

[9].Valsakumar AK, Valappil UC, Jorapur V,

Garg N, Nityanand S, Sinha N. Role of immunosuppressive therapy on clinical,

immunological, and angiographic outcome in active Takayasu's arteritis. J

Rheumatol 2003; 30:1793-8. [PubMed]

[10].Daina E, Schieppati A, Remuzzi G.

Mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of Takayasu arteritis: report of three

cases. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130:422-6. [Pubmed]

[11].Salvarani C, Magnani L, Catanoso M,

Pipitone N, Versari A, Dardani L, Pulsatelli L, Meliconi R, Boiardi L.

Tocilizumab: a novel therapy for patients with large-vessel vasculitis.

Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012; 51:151-6. [PubMed]

[12].Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, Brasington RD, Lenschow DJ, Liang P. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with difficult to treat Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:2296-304. [PubMed]

[Full text]

[13].Rao SA, Mandalam KR, Rao VR, Gupta

AK, Joseph S, Unni MN, Subramanyan R, Neelakandhan KS. Takayasu arteritis:

initial and long-term followup in 16 patients after percutaneous transluminal

angioplasty of the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta. Radiology 1993;

189:173-9. [PubMed]

[14].Qureshi MA, Martin Z, Greenberg RK.

Endovascular management of patients with Takayasu arteritis: stents versus stent

grafts. Semin Vasc Surg 2011;24:44–52.

[PubMed]

[15].Ishikawa K, Maetani S. Long-term

outcome for 120 Japanese patients with Takayasu's disease. Clinical and

statistical analyses of related prognostic factors. Circulation 1994;

90:1855-60. [PubMed]