Case Report

Spontaneous Bone Regeneration after Resection of an Unusually Aggressive Recurrent Central Giant Cell Granuloma in a Nigerian Adolescent

*,Olufemi Ogundipe, * Oluwafemi Ariyibi, *Ayodeji Egberongbe *Gb Akinwonmi

- * Oral Maxillofacial Surgery and Pathology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

- Submitted: Monday, November 28, 2016

- Accepted: Friday, January 20, 2017

- Published: Sunday, January 29, 2017

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Background

Aggressive variant of Central Giant Cell granuloma (CGCG) is rare and is characterized by the presence of pain, rapid growth, expansion and / or perforation of the cortex, and a high tendency to recur based on clinical and radiographic findings. It account for about a third of all cases of CGCG.

Case Presentation

A case of aggressive CGCG with early recurrence, rapid growth associated with pain and spontaneous bleeding is presented. Spontaneous bone regeneration with no evidence of recurrence was noted after 2.5 year follow-up. The factors responsible for spontaneous bone regeneration (SBR) are discussed.

Conclusions

This case illustrates the need for radical surgery in aggressive CGCG. High osteogenic potential in a growing mandible offers the possibility of bone regeneration.

Key words

Spontaneous bone regeneration, aggressive central giant cell granuloma, case report.

Introduction

Aggressive variant of CGCG is rare and is characterized by the presence of pain, rapid growth, expansion and / or perforation of the cortex, and a high tendency to recur based on clinical and radiographic findings [1]. It account for about a third of all cases of CGCG [1, 2].

Different options have been suggested for treatment ranging from medical therapy [3, 4] in Combination with enucleation/curettage and cryosurgery [5] to radical enbloc resection [6, 7]. Advocates of conservative surgery [8] in combination with medical therapy [4] suggest that this minimizes bone and tooth loss that can impair further bone growth particularly in children. However, risk of recurrence [1], failure [9, 10] and side effects of medical therapy [11] have been noted with the use of this strategy.

Jaw resection is often the last option in aggressive CGCG however, this produces functional and aesthetic critical size defects which can make reconstruction and rehabilitation very challenging. Vascularized bone graft and dental implant restoration has attendant donor site and cost implications.

Spontaneous bone regeneration (SBR) following continuity defect of the mandible is rare. Few case reports [12-19] have documented regeneration following trauma or ablative surgery mostly in young patient perhaps offering an alternate reconstruction option. This report presents the surgical management of an aggressive CGCG in a 12-year-old girl with spontaneous bone regeneration.

Case Report

A 12-year old Nigerian female presented at the Oral and Maxillofacial Clinic of the Federal Medical Centre, Owo with complaint of rapidly increasing mandibular swelling of three week duration. The swelling affected aesthetics, speech and mastication with associated grade III mobility of 44, 45, 46 and a tendency to bleed on gentle probing. Other aspects of the medical history were unremarkable. Examination revealed mandibular swelling which was firm, extending from 43 to 46 with bucco-lingual bone expansion. Jaw radiographs showed saucerization of alveolar bone in relation to 44-46 while the results of blood chemistry and routine laboratory tests were within normal limit.

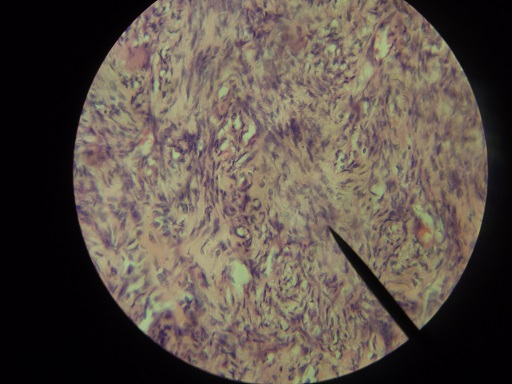

Enucleation and curettage of the lesion without preservation of 44, 45, 46 was undertaken under general anaesthesia which returned a histological diagnosis of CGCG of the mandible (Figure 1). Her immediate postoperative period was significant for recurrent swelling which was noticed 10 days after discharge. The rapidly increasing recurrent swelling extended from 43 to retromolar region (Figure 2) and was associated with spontaneous profuse bleeding (sometimes up to 100ml). She was reviewed by anaesthetist and Peadiatrician for severe anemia (PCV 21%) and anticipated difficult intubation due to huge mass lesion. Her INR, PT, PTTK, FBC, etc were all within normal range. Spontaneous bleeding was successfully managed by digital pressure with adrenalin soaked gauze, intramuscular vitamin K (100mg) and preoperative blood transfusion (2 pints of whole blood).

Figure 1- histological diagnosis of CGCG of the mandible

Figure 2-Rapidly increasing recurrent swelling extended from 43 to Retro-molar

Endo-tracheal intubation ETI was complicated by the mass lesion with associated profuse bleeding. This was overcome by the use of McCoy laryngoscope and bougie. Right segmental mandibular resection extending from 42 to the right angle of mandible was done via submandibular and gingival margin incisions. Estimated blood loss by visual assessment of suction bottle and soaked swabs was 1.2L and she received 2 pints of whole blood intra operatively. Potential airway obstruction due to inflammatory oedema from the difficult intubation and surgical procedure necessitated the retention of naso-trachea tube for 24 hours. She was discharged on day 7 after satisfactory healing and suture removal. She was maintained on monthly review for first six months and thereafter twice year for 2 years without evidence of recurrence (Figure 3 & 4) .

Figure 3 –Follow up after 6 Months

Figure 4 –Follow up after 2 years

At one-year follow-up visit, bone continuity was palpated at the operation site; bone regeneration was subsequently demonstrated on CT Scanogram (Figure 5).

Figure 5 –Bone regeneration on subsequent CT scan

Discussion

Previous reports of recurrence CGCG after enucleation/curettage of CGCG [1, 2, 9-10] highlight the biological behaviour of the aggressive variant. The early recurrence and rapid growth after enucleation/ curettage depicted in the present case is clearly suggestive of unusual aggressiveness. In addition, pain and spontaneous bleeding is another clinical marker of aggressiveness observed in the present report. Incidentally, rapid growth, tenderness and spontaneous bleeding are naturally associated with malignant disease and this may pose some diagnostic dilemma however the absence of mitosis or cellular pleomorphism clearly underscores the benign nature of the lesion.

Cytometric and immunocytochemical methods have shown that aggressive sub-types have a higher number and relative size index of giant cells , greater fractional surface area occupied by giant cells and higher mean cannibalistic giant cell frequency which may be of diagnostic and prognostic importance [17, 18]. This was not done in the present report due to lack of facilities.

The huge mass lesion and spontaneous bleeding of the reported case posed some anaesthetic challenges including shared airway, difficult intubation and potential postoperative airway obstruction. Standard anaesthetic techniques are usually effective in overcoming these. Radical surgery in the form of wide resection with a safety margin was preferred in this case and is recommended for huge size and extremely aggressive cases [9]. Concern about the effect of ablative surgery on further growth of the jaw [9] is clearly out-weighed by need for immediate loco-regional control of lesion to address esthetic, masticatory and speech problems. Another reason for radical surgery is for effective control of spontaneous bleeding which in this case became clinically significant and required active treatment. The cause of spontaneous bleeding and severe haemorrhage is not clear since CGCG is not regarded as a hemorrhagic lesion, trauma from opposing tooth may be a factor. Prompt replacement of lost blood and other local measures are important in the preoperative and intra-operative management.

In this case report, SBR was observed to bridge the continuity defect approximately in a similar manner to those previously reported [12-16]. Factors thought to promote SBR include young age, adequate soft tissue cover and jaw immobilization [14-15]. We believe that the high osteogenic potential of this young patient and the meticulous preservation of periosteum are crucial factors responsible for SBR. Jaw resection is rarely carried out in children because of the risk of impairment of further growth. Despite the radical nature of surgery, no impairment of mandibular growth was noted 2.5 years after initial surgery. Abdulai

et al., [16] reported same finding. In view of this, we opine that the claim of mandibular growth impairment following wide resection may be exaggerated. Although SBR is rare and does not occur in all young patients, we believe that the possibility of SBR should be entertained in growing children. SBR can potentially offer both economic and biologic cost saving benefits over other conventional methods of surgical reconstruction. The financial and psychological cost of multiple revision surgery for recurrent lesions after enucleation/curettage should be weighed against supposed growth disturbance of radical surgery. According to Sharma et al [19], some spontaneous regeneration should be anticipated and final reconstruction delayed until this is complete.

Conclusions

Radical surgery is indicated in very aggressive CGCG. SBR can potentially be of use where osteogenic potential is high. More studies on factors affecting SBR in continuity defect are needed.

Authors’ Contributions

Olufemi Ogundipe: conceived the study, carried out literature

search, participated in design and edited the final manuscript.

Oluwafemi Ariyibi: carried out literature search and

preparation of draft manuscript.

Ayodeji Egberongbe: carried out literature search and

preparation of draft manuscript.

Gb Akinwonmi: carried out literature search and

preparation of draft manuscript.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of Interests.

Ethical Considerations

The written informed consent for publication of this case report was taken from the next of kin of the patient. The consent is available with authors.

References

[1].Chuong R, Kaban LB, Kozakewich H, Perez- Atayde A. Central giant cell lesions of the jaws: a clinicopathologic study. J Oral MaxillofacSurg 1986; 44: 708–713. PMID3462363 [PubMed]

[2].Waldron CA, Shafer WG. The central giant cell reparative granuloma of the jaws: An analysis of 38 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1966; 45: 437-447. PMID5910047 [PubMed]

[3].de Lange J, van den Akker HP, van den Berg H. Central giant cell granuloma of the jaw: A review of the literature with emphasis on therapy options. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;104: 603-615. PMID17703964 [PubMed]

[4].Gupta B, Stanton N, Coleman H, White C, Singh JA novel approach to the management of a central giant cell granuloma with denosumab: A case report and review of current treatments. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015; 15:106- 107. PMID26032758 [PubMed]

[5].Webb DJ, Brockbank J. Combined curettage and cryosurgical treatment for the aggressive "giantcell lesion" of the mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg.1986; 15: 780-785. PMID3100684 [PubMed]

[6].Tosco P, Tanteri G, Iaquinta C, Fasolis M, Roccia F, Berrone S, Garzino-Demo P. Surgical treatment and reconstruction for central giant cell granuloma of the jaws: a review of 18 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2009; 37: 380-387. PMID19447638 [PubMed]

[7].Bataineh AB, Al-Khateeb T,Rawashdeh MA. The surgical treatment of central giant cell granuloma of the mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002; 60: 756-761. 12089688 [PubMed]

[8].Theologie-Lygidakis N, Telona P, Michail-Strantzia C, Iatrou I. Treatment of central giant-cell granulomas of the jaws in children: Conservative or radical surgical approach? Journal of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery 2011; 39: 639-644. PMID21208808 [PubMed]

[9]Roberts J, Shores C, Rose AS. Surgical treatment is warranted in aggressive central giant cell granuloma: a report of 2 cases. Ear Nose Throat 2009; 3: 8-13. PMID19291624 [Pubmed]

[10].Shirani G, Abbasi AJ, Mohebbi SZ ,Shirinbak I. Management of a locally invasive Central Giant Cell Granuloma (CGCG) of mandible: Report of an extraordinary large case. Journal of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery 2011; 39: 530-533. PMID21159518 [PubMed]

[11].El Hadidi YN, Ghanem AA, Helmy I. Injection of steroids intralesional in central giant cell granuloma cases (giant cell tumor): Is it free of systemic complications or not? A case report .Int J Surg Case Rep 2015; 8: 166–170. PMID25699662 [PubMed]

[12].Throndson RR, Johnson JM. Spontaneous regeneration of bone after resection of central giant cell lesion: a case report. Tex Dent J 2013; 12: 1201-1209. PMID24600804 [PubMed]

[13].Adebayo ET, Fomete B, Ajike SO. Spontaneous bone regeneration following mandibular resection for odontogenicyxoma. Ann Afr Med 2012; 11: 182-185. PMID22684138 [PubMed]

[14].Ahmad O, Omami G. Self-regeneration of the mandible following hemimandibulectomy for ameloblastoma: a case report and review of literature. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2015; 14(Suppl1): 245-250. PMID25861189 [PubMed]

[15].Ogunlewe MO, Akinwande JA, Adeyemo WL. Spontaneous regeneration of whole mandible after total mandibulectomy in a sickle-cell patient. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006; 64: 981-984. PMID16713818 [PubMed]

[16].Abdulai AE. Complete spontaneous bone regeneration following partial mandibulectomy. Ghana Med J 2012; 3: 174–177. PMID23661834 [PubMed]

[17].Sarode SC, Sarode GS. Cellular cannibalism in central and peripheral giant cell granuloma of the oral cavity can predict biological behaviour of the lesion. J Oral Pathol Med 2010; 6: 459-463. PMID24112367 [PubMed]

[18].O’Malley MP, Pogrel MA, Stewart JC, Silva RG, Regezi JA. Central giant cell granulomas of the jaws; phenotype and proliferation associated markers. J Oral Pathol Med 1997; 26: 159–163. PMID9176789 {pubMed]

[19].Sharma P, Williams R, Monaghan A. Spontaneous mandibular regeneration: another option for mandibular reconstruction in children? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 5: 63-66. PMID22578705 [PubMed]