Case Report

Poorly Cohesive Cells of the Colon Cancer: A New Pathological Entity? A Case Report and Literature Review

*Ali Koyuncuer

- *MD, Department of Pathology, Antakya Government Hospital, Hatay, Turkey

- Submitted Thursday, October 31, 2013

- Accepted Saturday, December 14, 2013

- Published Friday, January 24, 2014

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma a rare form of colorectal carcinoma associated with poor prognosis. In addition, the appearance of poorly cohesive cells is very rare in this type of cancer. In this case report, a 25-years-old man presented with abdominal pain and vomiting. A 5x2x2 cm infiltrative and constricting tumor in the sigmoid colon was observed and the patient underwent a sigmoidectomy. A review of the literature on poorly differentiated carcinoma –within areas of poorly cohesive cells– of the colon yielded no previously described cases. Clinically, colorectal carcinomas occur most frequently in patients after age of 40 year and incidence in men is slightly higher than among women. The etiology of malignant large bowel tumors is usually multifactorial. Colonic lesions in young adults must be distinguished from malignant tumors. We presented this case as an example of atypical clinical, radiological and histopathological findings.

Keywords

Poorly, cohesive cell, colon, carcinoma

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is common in the USA and is the third most frequently diagnosed cancer in both males and females. In 2011, it is estimated there were approximately 140,000 new cases and over 49000 deaths cause by colorectal cancer. Most tumors arise in the colon (about 72%) and, less commonly in the rectum (about 28%) [1]. Colorectal cancer affects approximately 875,000 people worldwide. The World Health Organization reports that colorectal cancer accounts for over eight percent of all new cancers [2]. On the whole, approximately 90% of cases develop in patients 50 and older [2]. The incidence of colorectal cancer has been reported as 102.6 and 76.7 per 100,000 among 55–59 year olds for men and women, respectively. The incidence rates increase among those aged 81 or older [3]. Colorectal cancer is very rare among young adults. Colorectal cancer occurs at a frequency of about 1% among 20-34 year olds [4]. The most frequent colorectal carcinoma type is adenocarcinoma. Large bowel carcinoma tumor grade is classified on the basis of gland involvement (gland formation) and solid or nesting, cords of cells. According to this grading system, well differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated colorectal cancers occur at frequencies of about 10%, 70%, 20%, respectively [5]. The etiological factors that have been implicated include high consumption of fat and animal protein, genetic polyposis syndromes, inflammatory bowel disease [6], obesity, smoking, alcohol, and oral contraceptive use [5]. We describe the case of poorly differentiated carcinoma containing areas of poorly cohesive cells in a 25-years-old man.

Case Report

Clinical Data and Presentation:

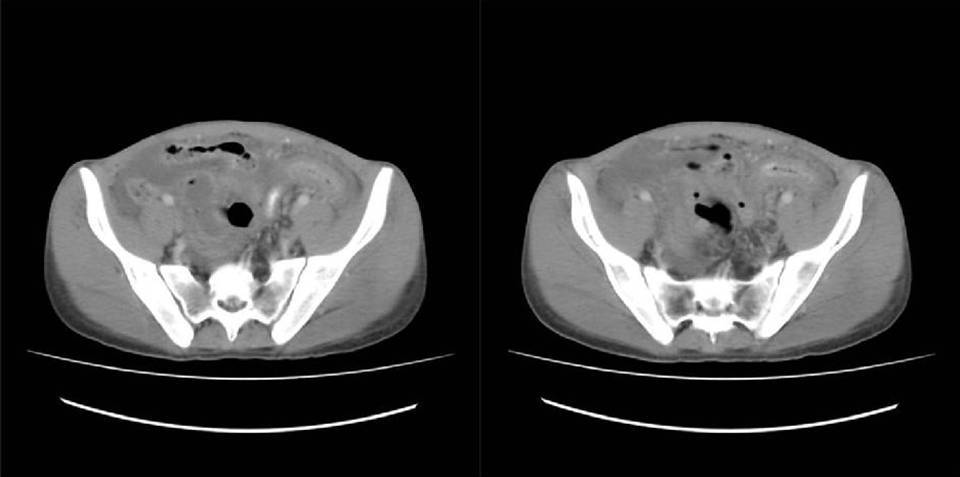

A 25-year-old man presented with abdominal pain and vomiting. Multislice computed tomography imaging showed diffuse thickening of the sigmoid colon and distal left (descending) colon (Figure 1). Peritoneal fluid was detected in the abdominal cavity. The clinical impression was that the lesion represented Crohn's disease. The patient underwent a sigmoid colectomy.

Figure 1: Multislice computed tomography imaging of the abdomen showing the diffuse sigmoid colon wall thickening.

Histopathologic Findings:

The macroscopic appearance:

The specimen was labeled sigmoid colon and consists of a segment of large bowel measuring 13 cm in length x 3.0 cm in average diameter (1 cm circumference proximal margin, 2 cm circumference distal margin) after fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Serial section of the specimen lesions revealed an ill-defined, gray-white firm infiltrative and constricting mass measuring 5x2x2 cm (distance from longitudinal margins, proximal 4 cm; distal 4 cm) (Figure 2). Polyp or ulceration were not present within the tumor. The tumor deeply invaded into the pericolic subserosal adipose tissue. The thickened intraluminal large bowel wall had caused partial obstruction. Macroscopic tumor perforation was not identified.

Figure 2: Gross Features: The macroscopic appearance of carcinomas in the sigmoidectomi specimen. Showing diffuse thickening of the bowel wall. The tumors show pronounced infiltration of the submucosa, with expansion of the subserosal adipose tissue. The lesion view demonstrates firmer, paler, completely flat and stenosing tissue.

Microscopic Features:

The malignant tumor appeared to predominantly consist of mononuclear inflammatory cells with strong a desmoplastic response. The stroma of carcinoma produced collagen. The tumors cells were composed of very little cytoplasm, relative nuclear polarity and variable nuclear pleomorphism. The nuclei of infiltrating malignant cells were densely hyperchromatic and resembled plasma cells (nucleus eccentrically placed). Mucosae, submucosa, muscularis propria and the subserosal adipose tissue infiltrated as isolated single cells, nests, and cords sheets of malignant cells. Intact colonic mucosa appeared in focal areas with malignant tumor cells [Figure 3A, B, C]. Mitotic figures were very rare. Perineural invasion was widely present. Focal areas of myxoid changes in the large bowel wall were present. Peritumoral infiltrate consisted of eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Evident malignant gland formation (including columnar and goblet cells) and necrosis was not present. Metastasis was present in five regional lymph nodes.

Figure 3A: Low power view demonstrating malignant tumor cells infiltrating and replacing normal colonic crypts or glands (Hematoxylin and Eosin, x40).

Figure 3B: Poorly Differentiated Carcinoma. High-power magnification demonstrating the presence of tumor inducing the desmoplastic reaction and poorly cohesive cells infiltrate (Hematoxylin and Eosin, x200).

Figure 3C: High-power view with no evident gland formation. This is a more cord-like and single cells infiltrating tissue (Hematoxylin and Eosin, x200).

Discussion

A report of poorly differentiated carcinoma containing areas of poorly cohesive cells of the sigmoid colon in a young adult has not been reported previously. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma is not encountered frequently. In Japan, 4.8% prevalence of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma was observed, while Yoshida et al. reported prevalence of about was 8% [7]. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas and undifferentiated carcinomas are also known as high-grade tumors. There is a decrease in the glandular architecture and mucus secretion [2]. In tumors, nuclear disarray with variation in nuclear size and shape are common [4]. The pathologist should be able to distinguish primary and secondary causes. The College of American Pathologists (CAP, Posted: June 15, 2012) determined that poorly cohesive patterns are not a common histologic type for primary carcinoma of the colon and rectum. On the contrary, poorly cohesive patterns or poorly cohesive carcinoma have been described in carcinoma of the stomach. For this diagnosis, poorly cohesive carcinoma must contain signet-ring cell features or other patterns (poorly cohesive carcinoma type) similar to mononuclear inflammatory cells in more than half of cases [8]. On the other hand, not all signet ring cell carcinomas of the colorectal tissue contain eccentrically displaced nuclei [4]. In our case, signet-ring cell features were not observed. In our case consisted of eccentrically placed nuclei with coarse chromatin granules in the tumor cells. In other words, in our case tumor cells resemble plasma cells in microscopic appearance.

The differential diagnosis of bowel wall thickening by computed tomography includes both benign and malignant conditions. Radiologic thickening of the bowel wall may be cause by hemorrhage or hematoma, infarct, neoplasm, or Crohn’s disease [9]. The histopathology of this tumor must be differentiated from poorly cohesive carcinoma of the stomach, signet ring cell carcinomas of the colon, poorly cohesive cell carcinomas of the gallbladder, linitis plastica, and plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas. It is known that diffuse type gastric carcinomas infiltrate the stomach wall with decreased or absent gland structure. Microscopically, the nuclear features of diffuse carcinomas generally include the presence of round and small single cells with cytologic features. Tumours display less mitotic activity than expected. Mucin, desmoplasia and inflammation may also be present [10]. In this case, desmoplasia and inflammation was seen in accordance with the literature.

World Health Organization (WHO) reported poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas in the gallbladder the tumor occur within glands at a rate of 5-39% however [11], World Health Organization 2010 investigated new alternative designations and morphological definitions. Patel el al (the current definition of poorly cohesive cell carcinomas) observed tumors in women more commonly than among men with a mean age of 63. Microscopically, the characteristic features of poorly cohesive carcinomas are the presence of small bland-monotonous cells with cytologic features. Nuclear features resemble invasive lobular breast carcinoma and urothelial plasmacytoid carcinoma [12]. Linitis plastica is seen rarely in the colon and rectum. Linitis plastica of the colon is may involve glands and signet ring cells [4]. Signet ring cell adenocarcinoma is uncommon in colorectal tissue and may occur at a younger age. Generally, it involved glands consisting of signet ring cells and mucin accumulation [5]. Unlike in our case, less mucin and absent signet ring cell are typical of this condition. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas (at first reported) are very rare cancers of the urinary bladder, and in the past were confused with multiple myeloma [13]. Microscopically, the characteristic feature of plasmacytoid variants was the presence of single cells (plasmacytoid appearance), eosinophilic cytoplasm and small nucleoli cells with cytologic features. This tumor is associated together with high grade disease [14]. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas are seen in individuals between 41 to 81 years and more than 50% patients are women. About 40% of cases include lymph node involvement and 33% cases include involvement of abdominal peritoneal surfaces [15]. Several parameters in the pathologic staging (pTNM) include regional lymph node metastasis, lymph-vascular invasion, presence of residual tumor, positive surgical margins, pre-operative elevation of carcinoembryonic antigen elevation, tumor grade and similar factors [16]. Lan et al. reported 5-year survival rates of 86.3% in stage I disease, 79.2% in stages II, 65.4% in stages III and 12.8% among individuals with stage IV disease [17]. Another review reported 5-years survival rates of 6% with presence of distant metastases [3].

As a result, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma cases are rarely seen in young adults. They involve diffuse infiltrative patterns invading the wall of the large bowel and are associated with poor prognosis. Therefore, ruling out the possibility of malignant tumor in a young adult is very important. In spite of the fact that the definitions are similar for poorly cohesive carcinoma in both the stomach and gallbladder, the new definition and designation was not applicable in the colon and rectum. We believe that use of new criteria can identify poorly cohesive cell carcinoma. The diagnosis of this group of colorectal carcinomas is necessary. Early diagnosis and treatment prolongs the patients’s life duration.

Consent

The study was approved by the Antakya Government Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB), and all participants signed an IRB-approved consent form before participation in the study.

List of abbreviations

World Health Organization (WHO)

Pathologic staging (pTNM)

Competing interests

Non-financial competing interests

Funding

None

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to Volkan Adsay for their contribution to the practice

Reference

[1]Cancer.org [Internet]. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc.; ©2011 [updated 2011 Oct 1; cited 2012 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-028323.pdf

[2]Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kudo S, Riboli E, Nakamura S, Hainaut P, Rubio CA, Sobin LH, Fogt F, Winawer SJ, D.E. Goldgar DE, Jass JR. Tumours of the Colon and Rectum. In Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System, World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Edited by Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000:103-43.

[3]Quarini C, Gosney M: Review of the evidence for a colorectal cancer screening programme in elderly people. Age Ageing 2009, 38:503-8.

[4]Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Noffsinger AE, Stemmermann GN, Lantz PE, Isaacson PG. Epithelial Neoplasms of the Colon. Gastrointestinal Pathology: An Atlas and Text, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &s Wilkins; 2008:898-1035.[Pubmed]

[5]Redston M: Epithelial Neoplasms of the Large Intestine. In Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas. 2nd edition. Edited by Odze RD, Goldblum JR. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:597-638.

[6]Rosai J (Ed): Rosai and Ackerman’s Surgical Pathology. 10th edition. New York: Mosby Elsevier, 2011.

[7]Yoshida T, Akagi Y, Kinugasa T, Shiratsuchi I, Ryu Y, Shirouzu K: Clinicopathological study on poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the colon. Kurume Med J 2011, 58:41-6.[pubmed]

[8]Tang LH, Berlin J, Branton P, Burgart LJ, Carter DK, Compton CC, Fitzgibbons P, Frankel WL, Jessup J, Kakar S, Minsky B, Nakhleh R, Washington K: Protocol for the Examination of Specimens From Patients With Carcinoma of the Stomach [Internet]. Washington:College of American Pathologists (CAP); © 1996-2010 [updated 2012 June; cited 2012 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.cap.org

[9]Macari M, Balthazar EJ: CT of bowel wall thickening:significance and pitfalls of interpertation. AJR Am Roentgenol 2001, 176:1105-16[pubmed]

[10]Fenoglio-Preiser C, Carneiro F, Correa P, Guilford P, Lambert R, Megraud F, Muñoz N,Powell SM, Rugge M, Sasako M, Stolte M, Watanabe H: Tumours of the Stomach. In Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System, World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Edited by Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000:37-67

[11]Albores-Saavedra J, Scoazec JC, Wittekind C, B. Sripa, Menck HR, Soehendra N, Sriram PVJ: Carcinoma of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System, World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Edited by Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000:206-17.

[12]Patel S, Roa JC, Bagci P, Tapia O, Jang KT, Lim M, Dursun N, Saka B, Ducato L, Basturk O, Sarmiento J, Adsay NV: Poorly Cohesive Cell (Diffuse-Infiltrative/Signet-Ring)Carcinomas of the Gallbladder (GB): Clinicopathologic Analysis of 24 Cases Identified in 628 GB Carcinomas. Modern Pathology 2012, 25(Suppl 2):421-422

[13]Sahin AA, Myhre M, Ro JY, Sneige N, Dekmezian RH, Ayala AG. Plasmacytoid transitional cell carcinoma. Report of a case with initial presentation mimicking multiple myeloma. Acta Cytol 1991, 35:277-80.[pubmed]

[14]Lopez-Beltran A, Sauter G, Gasser T, Hartmann A, Schmitz-Dräger BJ, Helpap B, Ayala AG,Tamboli P, Knowles MA, Sidransky D, Cordon-Cardo C, Jones PA, Cairns P, Simon R, Amin MB, Tyczynski JE. Infiltrating urothelial carcinoma. In Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs, World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Edited by Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Isabell A. Sesterhenn IA. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004:89-157.

[15]Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Nguyen M, Gokden N, Sangoi AR, Presti JC Jr, McKenney JK: Plasmacytoid carcinoma of the bladder: a urothelial carcinoma variant with a predilection for intraperitoneal spread. J Urol 2012, 187:852-5.[pubmed]

[16]Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, Conley B, Cooper HS, Hamilton SR, Hammond ME, Henson DE, Hutter RV, Nagle RB, Nielsen ML, Sargent DJ, Taylor CR, Welton M, Willett C: Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000, 124:979-94.[pubmed]

[17]sLan YT, Yang SH, Chang SC, Liang WY, Li AF, Wang HS, Jiang JK, Chen WS, Lin TC, Lin JK: Analysis of the seventh edition of American Joint Committee on colon cancer staging. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012, 27:657-63.[pubmed]