Case Report

Cardiogenic Shock with Acute Myocardial Ischemia after Successful Conservative Treatment for Infective Endocarditis: Case Report

* Yuka Sakurai, *Takashi Ando, *Kiyoshi Chiba, *Hirokuni Ono *Yosuke Kitanaka, *Masahide Chikada,*Takeshi Miyairi.

- *Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, St. Marianna University School of Medicine, Kanagawa, Japan

- Submitted Thursday, September 25, 2014

- Accepted:Monday, December 08, 2014

- Published Monday, December 22, 2014

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

A febrile 81-year-old patient admitted for back pain was diagnosed with Streptococcus viridans infection. Thoracic echocardiography revealed infective endocarditis (IE), aortic valve vegetation, and mild aortic regurgitation, despite an ejection fraction of 60% and normal left ventricular wall motion. Antibiotic therapy was initiated with penicillin G (2,400,000 IU/day) and gentamycin (120 mg/day). On day 14, white blood cell counts had decreased from 10,700 to 5200/L and C-reactive protein from 10.2 to 1.3 mg/dL, without embolization. On day 20, she developed acute myocardial infarction corroborated by elevated CK-MB (102.4 IU/L). Coronary arterial angiography revealed triple vessel disease, including left main trunk stenosis. The non-coronary cusp of the aortic valve was perforated and herniated toward the left ventricle. Concomitant aortic valve replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting at the three sites were successful. Postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient did not require antibiotics or warfarin at a 6-month follow-up visit.

Key words

acute aortic regurgitation, infective endocarditis, acute myocardial infarction

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is generally an endovascular bacterial infection affecting native heart valves and intravascular implants, such as pacemaker electrodes or valvular prostheses. The severity of native aortic valve IE varies from clinically silent to life-threatening, which complicates early detection.Conservative antibiotic therapy usually resolves systemic inflammation and prevents heart failure and coronary embolism. However, acute aortic regurgitation (AR) often cannot maintain circulatory dynamics due to acute heart failure. Despite recent advances in treatment, IE remains associated with high morbidity and a mortality rate of 20%–30%. Most cases of coronary embolism occur in the native mitral valve. We present a rare case of native aortic valve IE diagnosed in a febrile patient admitted for back pain. During antibiotic therapy, the patient received successful emergency aortic valve replacement and coronary artery bypass procedure because of acute myocardial infarction.

Case Report

An 81-year-old woman was transported to an emergency department with lower back pain, persistent fever, and general fatigue. Spine X-ray revealed a lumbar compression fracture. Medical history included a treatment for cavity-related bacteremia that she recently interrupted. At the time of admission, her body temperature was 35.9°C after receiving an antifebrile drug. Her blood pressure was 88/52 mmHg, and her heart rate was regular with 69 beats/min. The patient exhibited murmurs during the contraction phase, as exaggerated heart sounds (Levine III/IV) were detected on the right side, at the second rib interspace. Oxygen saturation at room air was 95%, and air entered the lungs normally. Blood analysis indicated anemia (hemoglobin: 10.2 g/dL; normal: 12.1–15.0 g/dL) and a hyperinflammatory state detected by elevated white blood cell count (WBC: 10,700/L; normal: 4500–10,000/L) and C-reactive protein (CRP: 8 mg/dL; normal: <1 mg/dL). Blood culture analysis identified a Streptococcus difficile strain susceptible to antibiotics.

An electrocardiogram presented a normal sinus rhythm, and a chest X-ray showed no pulmonary edema or cardiomegaly. However, transthoracic echocardiography revealed vegetation on the native aortic valve, with mild AR. We also detected aortic valve stenosis with annular calcification, without left ventricular asynergy or low kinetic energy. Enhanced computed (CT) also illustrated no embolization in any organ. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with IE and vegetation of the aortic valve.

A conservative treatment was initiated for her IE, namely penicillin G (2,400,000 IU/day) and gentamycin (120 mg/day) by intravenous drip. On the second day of medication, fever was alleviated, and bacteria were no longer detected in blood cultures. After 1 week, a second echocardiography showed that the aortic vegetation persisted but did not expand (<5 mm). On the 14th day of treatment, blood analysis also showed improvements in WBC (5200/L) and CRP (1.3 mg/dL).

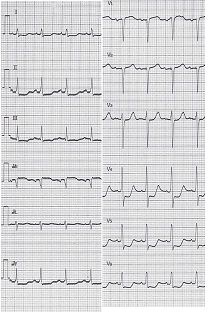

On the 20th day of treatment, the patient suddenly developed dyspnea, immediately after intubation for difficult breathing. An electrocardiogram revealed acute myocardial infarction (Figure 1) which was corroborated by an elevation in the cardiac marker CK-MB (102.4 IU/L). Chest X-ray presented butterfly opacities typical of pulmonary edema, with enlargement of the cardiac silhouette. Echocardiography showed cardiogenic shock, with severe acute AR, and a low (10%) ejection fraction. These symptoms could not rule out coronary embolism of the vegetation. Therefore, we immediately performed coronary angiography, which revealed triple vessel disease with left main trunk stenosis. Consequently, the patient did not have coronary embolism but organic stenosis (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Sudden complications on the 20th day of antibiotic treatment. Electrocardiogram showing ST segment elevation in all leads.

Figure 2: Coronary angiography clearly indicating triple vessel disease with organic stenosis but without embolism.

Emergency coronary artery bypass grafting was conducted. The vegetation and infected leaflets were carefully resected. The non-coronary cusp of the aortic valve was perforated and herniated toward the left ventricle. There was no abscess within the aortic annulus. Therefore, we performed biological prosthetic aortic valve supra-annular replacement (CEP Magna; 19 mm). During this operation, we also conducted triple coronary artery bypass grafting with saphenous vein grafts: single-vessel bypass to the left anterior descending artery, [2] single-vessel bypass to the first diagonal, and single-vessel bypass to the posterior descending artery.

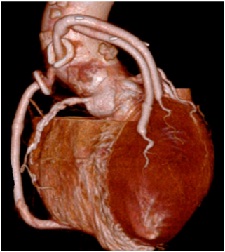

The postoperative course was uneventful, and antibiotic therapy was continued for 6 weeks. Postoperative echocardiography indicated that the prosthetic aortic valve was functioning normally with good contractions. 3D CT of the coronary artery showed all three patent grafts

(Figure 3). Laboratory tests were normal for WBC (6000/L) and CRP (0.02 mg/dL). The patient was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital, where she received treatment for her lumbar compression fracture, without any complication. At a 1-year follow-up visit to our outpatient clinic, the patient did not require antibiotics or warfarin.

Figure 3:Patient conditions after coronary artery bypass grafting. 3D computed tomography showing graft patency.

Discussion

Acute myocardial infarction due to coronary artery embolism is a common complication of IE [1-6]. In fact, coronary artery embolism is reported in 2% of IE patients. However, when minute embolisms are included, autopsy analyses reveal an incidence of 30%. Embolic occlusion occur more frequently in the left coronary artery than in the right coronary artery [7] because of the difference in blood flow and anatomical position [6, 7]. Most cases of embolic occlusion worsen even after coronary angiography, often leading to death [5]. The authors suggested that annular abscess formation is a risk factor for embolism [5, 6]. Our case did not show an abscess or embolism but triple vessel disease with organic stenosis.

The conservative antibiotic therapy was highly effective because it improved both the inflammatory scores and general condition of the patient. However, her circulation suddenly worsened unexpectedly because of acute AR and acute myocardial infarction. Thuny et al, reported that vegetation length was the most potent predictor of embolic events in IE patients [6]. However, they did not consider the degree of friability of the vegetation around the infected tissue [6]. In fact, the degree of friability of the vegetation was identified as a predictor of embolic events in IE patients [7]. Our case did not suffer an embolic event but sudden friability of the infected aortic valve leaflet. Therefore, further studies are needed to identify more adequate antibiotic therapy regimens for IE patients.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors’ contribution

YS: carried out the literature search and prepared the draft manuscript, carried out the experiments and interpreted the results, designed the study and performed the analysis, conceived the study, participated in design and edited the final manuscript.

TA: carried out the literature search and prepared the draft manuscript, carried out the experiments and interpreted the results, designed the study and performed the analysis, conceived the study, participated in design and edited the final manuscript.

KC: carried out the literature search and prepared the draft manuscript

HO: carried out the literature search and prepared the draft manuscript

YK: carried out the experiments and interpreted the results,

MC: carried out the experiments and interpreted the results,

TM: conceived the study, participated in design and edited the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

None

Funding

None Declared

References

[1].Ertan U, Ulas B, Goksel K, Baki K. Coronary embolism complicating aortic valve endocarditis:Treatment with successful coronary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol 2007; 119: 377–9.[Pubmed]

[2].Mikio Y, Yoshiro I, Tetsuo K, Otsu W, Toru K, Yoshiaki M, et al. A Case of Infectious Endocarditis with Inferior Myocardial Infarction. JCLS 2005; 53: 537–9.

[3].3.Noji S, Kitamura N, Yamaguchi A, Shuntoh K, Kimura S, Koh T. [Successful surgical treatment of active infective endocarditis associated with perforation of aortic wall]. Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1995 Jan; 43(1):69-73.[Pubmed]

[4].Maria CM, Isidre V, Jose ASR, Paloma A, Cristina S, Daniel L, et al. Acute coronary syndrome in infective endocarditis. Rev Esp Cardiol 2007; 60: 24–31 [Pubmed]

[5].Naoto M, Hiroyuki T, Mikiko M, Koso E, Satoru H, Makoto S.Aortic Valve Replacement and CABG for Aortic Stenosis and Unstable Angina Combined with Active Infective Endocarditis. Jpn J Cardiovasc Surg 2002; 31: 136–8. [Abstract]

[6].Thuy F, Habib G, Dolley YL, Canault M, Casalta JP, Verdier M et al. Circulating matrix metalloproteinases in infective endocarditis: a possible marker of the embolic risk. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e18830 [Pubmed]

[7].Prevention and treatment guidelines of infective endocarditis. Jpn Circ J 67(Suppl 4): 1039–82 (in Japanese).