Original Article

Neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy in the multidisciplinary treatment of rectal cancer

1Piero Rossi, 1Flavio De Sanctis, 1Edoardo Ricciardi, 1Mauro Montuori, 1Valerio Balassone, 4Giampiero Palmieri, 2Michaela Benassi, 3Matteo Vergati, 3Mario Roselli, 1Giuseppe Petrella

- 1U.O.C.D. complessa di Chirurgia Generale, Policlinico Tor Vergata, Roma, Direttore Prof. Giuseppe Petrella

- 2Unità di Radioterapia, Policlinico Tor Vergata, Roma, Direttore Prof. Riccardo Santoni

- 3U.O.S.D. Oncologia Medica, Policlinico Tor Vergata, Roma, Direttore Prof Mario Roselli

- 4U.O.S.D. Istopatologia dei trapianti d’Organo

- Submitted: March 25, 2013;

- Accepted: May 07, 2013;

- Published: May 08, 2013

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Rectal cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the Western world. More than 50% of tumours are diagnosed at a locally advanced stage. The multidisciplinary approach is the gold standard in the treatment of rectal cancer. With total mesorectal excision (TME), introduced by Heald R. J, and the development of specific neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy treatments (NRCT), a significant impact in local recurrence rates, downsizing, down staging, clinical complete response (cCR) and pathological complete response (pCR) has been reached. NRCT and surgery are the most important determinants in reaching pCR and local control of disease.

Materials and Methods

A total of 11 patients (with stage II and III rectal cancer treated in our Institute between 2004 and 2011 were included in our study: 5 males and 6 females, average age 67,82 (range 54-77 years). In all patients, the diagnosis was performed with colonoscopy and histology. The staging in all patients was carried out with a total body CT scan and a trans-rectal ultrasound examination. All patients underwent long-course neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy (details in table).

Results

All but one of the patients is still alive. No patient had local recurrence at follow up; pCR was observed in 4 patients; downstaging was seen in 5 patients; no response was observed in 2 patients. The results of the multidisciplinary treatment of our cases are shown in table 1. In 4 cases, it was necessary to briefly discontinue the NRCT treatment due to toxicity. We had no complications in the peri-operative period. One male patient is suffering “impotentia erigendi”, and 2 patients report impaired defecation.

Discussion

Treatment of rectal cancer has dramatically improved over the last twenty years. Before the introduction of TME, the local recurrence rates were between 20 and 40%. In recent decades, NRCT has emerged in the treatment of stage II-III rectal cancer. In particular, the EORTC study showed that the association of NRCT treatment combined with surgery has a considerable impact about reduction of local recurrence rates: they are at 7.6%. NRCT is well tolerated by patients. We can state the efficacy of NRCT in the absence of correlated peri-operative morbidity.

Introduction

Rectal cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the Western world [1, 2, 3]. More than 50% of tumours are diagnosed at a locally advanced stage.

The multidisciplinary approach is the gold standard in the treatment of rectal cancer. With total mesorectal excision (TME), introduced by Heald R. J. [4, 5, 6, 7], and the development of specific neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy treatments (NRCT), a significant impact in local recurrence rates, downsizing, down staging, clinical complete response (cCR) and pathological complete response (pCR) has been reached. Total mesorectum excision allows a reduction of local recurrence rate to 10% while pre-TME surgery local recurrence rates are 20-40% [4, 5, 6, 7].

Studies into neoadjuvant radiotherapy treatments by Phelam et al. in 1980 [8] and Bekdash et al. in 1990 [9], demonstrated a favourable impact on local recurrence. Later, Sauer et al. in 2004 [10], studies in 2006 by the FFCD (Fédération Francophone de la Cancérologie Digestive) and by the EORTC (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer) [11] demonstrated the efficacy of NRCT in reduction of local recurrence.

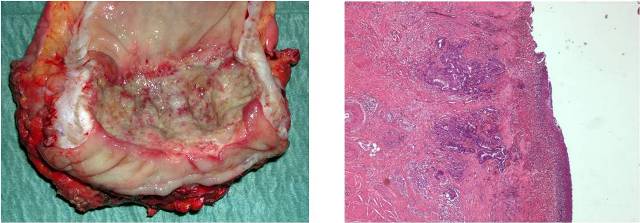

Image 1: Histology: Adenocarcinoma mildly differenziated (G2), extensively ulcerated, infiltrating bowel's wall until to peri visceral's tissues, with large aspects of regression and fibrosis.

NRCT and surgery are the most important determinants in reaching pCR and local control of disease. An interval ≥ 8 weeks between the end of neoadjuvant treatment and surgery correlates with an higher rate of pCR and a lower rate of local recurrence [12]. More studies are needed to determine the ideal interval. pCR also shows itself to be an important clinical predictor for local control and disease-free survival. pCR, also represents an important pre-surgical criterion in increasing the number of sphincter-saving procedures [8, 9, 10, 11]. The low specificity and sensitivity of imaging techniques in post-NRCT evaluation and restaging are still a matter of debate. In literature, it has been shown that the expression of some histopathological tumour markers can be related to a pCR or near-complete pathologic response. The positivity of lymph nodes after NRCT is also an important predictor of recurrent systemic disease [5, 13]. This retrospective study aims to report the results of NRCT in a small, but homogeneous, series of patients.

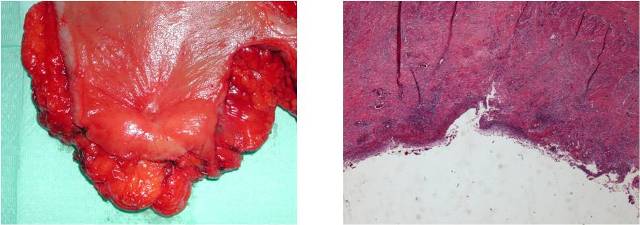

Image 2: Histology: Ulcerated area of mucosal on an sclerosis area trans mural, focally seat of chronic inflammation granulomatous giant. Bowel wall surrounding submucosal fibrosis and hypertrophy of the muscularis mucosal. Neoplastic tissue not reperted.

Material and Methods

A total of 11 patients (with stage II and III rectal cancer treated in our Institute between 2004 and 2011 were included in our study: 5 males and 6 females, average age 67, 82 (range 54-77 years). In all patients, the diagnosis was performed with colonoscopy and histology. The staging in all patients was carried out with a total body CT scan and a trans-rectal ultrasound examination. All patients underwent long-course neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy (details in table). Post-treatment re-staging was performed on all patients via EUS (Endorectal Ultra-Sound) and colonoscopy. All patients received standard surgery via laparotomy, including excision of the mesorectum and regional lymph nodes, being performed in all patients after an interval of about 6-8 weeks following completion of the neoadjuvant treatment. Median duration of follow-up was 40 months (3.33 years), range 4 to 102 months (8.5 years). Eight low anterior rectal resections (LAR) and three Abdomino Perineal Resection (APR) were performed. All but one of the patients who underwent LAR received protective ileostomy. Details are reported in table 1. A program of adjuvant chemotherapy was undertaken by all patients except one who refused.

| N |

Date of surgery |

Id |

F-UP (month) |

Age |

Gender |

cTNM |

Type of Surgery |

pTNM |

Time between NRCT and surgery

(weeks)

|

NRCT |

TOXICITY |

Distance

to A.M.

|

Results |

| 1 |

15/01/2004 |

VMG |

102 |

68 |

F |

cT3N0M0 |

LAR |

pT3N0Mx |

7 |

4500 cGy

5 Fu + oxaliplatin

|

No |

7 cm |

No Response |

| 2 |

02/09/2004 |

SF |

95 |

66 |

M |

cT3N1M0 |

LAR |

pT0N0M0 |

8 |

4500 cGy

Capecitabine

|

No |

8 cm |

pCR |

| 3 |

19/11/2007 |

IG |

56 |

68 |

F |

cT3N0M0 |

LAR |

pT3N0Mx |

6 |

4500 cGy

Capecitabine

|

Yes |

7 cm |

No Response |

| 4 |

10/04/2008 |

BE |

51 |

67 |

F |

cT3N1M0 |

LAR |

pT2N0Mx |

8 |

4500 cGy

Cisplatin+

Capecitabine

Boost 500 cGy

|

Yes |

7 cm |

Downstaging |

| 5 |

29/04/2008 |

AR |

51 |

69 |

M |

cT3N1M0 |

LAR |

pTxN1Mx |

7 |

4500 cGy

Cisplatin+

Capecitabine

Boost 500 cGy

|

No |

8 cm |

Downstaging |

| 6 |

15/03/2010 |

RR |

28 |

63 |

M |

cT3N1Mo |

LAR |

pT2N0M1 |

8 |

4500 cGy

Cisplatin + Capecitabine

Boost 540 cGy

|

No |

7 cm |

Downstaging |

| 7 |

18/10/2010 |

GM |

21 |

77 |

M |

cT3N1M0 |

APR |

pT0N0M0 |

|

Unknown |

Yes |

4 cm |

pCR |

| 8 |

09/05/2011 |

CA |

14 |

65 |

F |

cT3N0M0 |

LAR |

pT0N0M0 |

8 |

5040 cGy

Capecitabine

|

Yes |

7 cm |

pCR |

| 9 |

22/09/2011 |

NV |

10 |

72 |

F |

cT3N1M0 |

APR |

pT0N0M0 |

7 |

4500 cGy

Cisplatin+

Capecitabine

|

No |

3 cm |

pCR |

| 10 |

05/12/2011 |

PG |

8 |

54 |

M |

cT3N0M0 |

APR |

pT2N0M0 |

8 |

4500 cGy

Capecitabine

|

No |

4 cm |

Downstaging |

| 11 |

22/03/2012 |

MA |

4 |

77 |

F |

cT3N1M0 |

LAR |

pT2N1M0 |

7 |

4500 cGy

Capecitabine

|

No |

8 cm |

Downstaging |

Result

All but one of the patients are still alive. No patient had local recurrence at follow up; pCR was observed in 4 patients; down staging was seen in 5 patients; no response was observed in 2 patients. The results of the multidisciplinary treatment of our cases are shown in table 1. In 4 cases, it was necessary to briefly discontinue the NRCT treatment due to toxicity. We had no complications in the peri-operative period. One male patient is suffering “impotentia erigendi”, and 2 patients report impaired defecation.

One male patient with rectal cancer clinically T3N1 showed upon PET-CT an undefined area of hypodensity (14 mm) in the 8th hepatic segment. A contrast enhanced ultrasound with sonoVue® showed no metastatic lesions in the liver. He underwent a NRCT with Cisplatin and Capecitabine, a CT scan performed after the NRCT confirmed the presents of an incresead lesion in the 8th hepatic segment. 8 weeks after the end of radio-chemotherapy, he underwent LAR and core biopsy of the lesion in the hepatic dome that resulted a metastasis (15-3-2010). The patient followed a course of first line chemotherapy (FOLFIRI + Bevacizumab) and approximately one year later (3-5-2011), underwent liver resection and closure of the ileostomy; histologically, the metastasis resulted completed necrotic.

Another male patient suffering from rectal cancer cT3N1 underwent NRCT with Cisplatin-Capecitabine. 7 weeks from the end of the neo-adjuvant treatment, he underwent anterior resection and ileostomy (29-04-2008) and following adjuvant chemotherapy (Oxaliplatin-Xeloda). During the follow-up, due to liver metacronous metastasis, a right hepatic resection (19-5-2010) was performed. Despite chemotherapy with Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin, the patient died in July 2012 from recurrence of liver and lung metastasis.

Discussion

Treatment of rectal cancer has dramatically improved over the last twenty years. Presently, the multidisciplinary approach is the gold standard for the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. All scientific literature refers to TME proposed by Heald R.J.

Before the introduction of TME, the local recurrence rates were between 20 and 40%. Data reported by Heald gave evidence of local recurrence rates of around 10% [4, 5, 7]. In recent decades, NRCT has emerged in the treatment of stage II-III rectal cancer. In 1980, Phaleman et al, demonstrated a reduction in local recurrence rates in patients treated with preoperative RT compared to patients treated with adjuvant RT: local recurrence rates were 12% and 21% [8] respectively. In 1990, Bekdash et al. compared local recurrence rates in patients treated with pre-operative short-course RT followed by surgery and patients treated only with surgery: local recurrence rates were 11% and 27% respectively [9]. In 2004, Sauer et al. compared local recurrence rates in patients receiving neoadjuvant RCT coupled with adjuvant chemotherapy and patients treated only with adjuvant radiochemotherapy: local recurrence rates were 6% and 13% respectively. Overall survival at 5 years was comparable [10]. In 2006, a study of FFCD showed that pre-operative RCT reduces local recurrence rates compared to preoperative RT only: local recurrence rates were 8.1% and 16.5% respectively. In 2006, the study of EORTC 22921 Trial showed that neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy associated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy can significantly reduce local recurrence rates to 7.6%. Overall survival at 5 years was comparable [11]. In particular, the EORTC study showed that the association of NRCT treatment combined with surgery has a considerable impact about reduction of local recurrence rates: they are at 7.6%. NRCT is well tolerated by patients. NRCT protocols are presently the standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer [11, 14]. The optimal interval for surgery is ≥ 8 weeks after completion of NRCT, being related to an improved response to neoadjuvant treatment and a better prognosis [12]. Our case series, although limited, confirms the adequacy of the interval ≥ 8 weeks between the end of NRCT and surgery in treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: we recorded 4 pCR (1 patient with a 7-week interval and 3 patients with a 8-week interval), and 4 down staging (1 patient with a 7-week interval and 4 patients with a 8-week interval) out of 11 cases. 1 out of two patients with a no response had 6-week interval. This high percentage can probably be attributed to an initial over-staging. At follow up, peri-operative complications and local recurrences did not appear. Our results are similar to data in scientific literature in terms of response to NRCT treatment and in terms of local control recurrence. Accurate staging of the tumour to define the degree of parietal infiltration (radial margins) and the state of the mesorectal lymph nodes, both before and after NRCT treatment are necessary. We reported favourable results in down staging, downsizing, and decreased local recurrence rates in the combined treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. In literature, there is no evidence as to the impact of NRCT correlated to overall survival and disease-free survival. The possibility of down staging and the chances of sphincter preservation surgery are under discussion. Should the extent of surgery be planned according to preliminary cTNM or as detected by imaging techniques after? Certainly, Miles operation is necessary in cases with the tumour located at the ano-rectal junction and infiltrating the floor of the elevators. Unfortunately, despite advances in imaging techniques, the rate of complete clinical response may not coincide with a pCR.

From the above, the rationality of neoadjuvant RCT, in terms of reduction of local recurrence is evident. On the other hand, the continual evolution of imaging, and awareness of the prognostic value of the circumferential margin, along with the policy of “watch and wait” in highly-selected patients, has opened up a completely new scenario [15, 16].

Results are influenced by various factors, such as patient selection, the quality of pre-operative imaging, the neoadjuvant treatment, the interval between the ending of neoadjuvant RCT and surgery, the surgical technique and the quality of the anatomo-pathological examination. From this, the necessity of standardization of the diagnostic-therapeutic path is evident; lacking a uniform International consensus regarding the optimal management of rectal cancer patients has yet to be developed. However, recommendations and guidelines have been published [16, 17].

Moreover, complete tumour regression may develop after neoadjuvant chemo radiation therapy for distal rectal cancer. Studies have suggested that selected patients with complete clinical response may be able to avoid radical surgery and close surveillance may provide good outcomes with no oncologic compromise. However, the definition of complete clinical response is often imprecise and may vary between different studies. Definition of a complete clinical response should be based on very strict clinical and endoscopic criteria [18]. At present, the definition of cCR is still inconsistent, with only partial concordance with pCR. Patients who are observed, but subsequently fail to maintain a cCR, may have a worse outcome than those who undergo immediate tumour resection. Therefore, the rationale of a “watch and wait” policy relies mainly on retrospective observations from a single series. Proof of principle in small low rectal cancers, where clinical assessment is easy, should not be extrapolated uncritically to more advanced cancers where nodal involvement is common. Long-term prospective observational studies with more uniform inclusion criteria are required to evaluate the risk versus benefit [19].

Pathologic complete response (pCR) to neoadjuvant CRT is an important prognostic factor in locally advanced rectal cancer. However, it is uncertain if histopathological techniques accurately detect pCR. Therefore, biomarkers (EGFR, VEGF, CEA, GH, COX, thymidylate synthetase, mutations K-ras and p53) are undergoing continuous evaluation, in order possibly to allow better histopathological definition and, at the same time, predict a possible complete response to NCRT, and therefore better patient selection for the watch and wait policy [12, 20, 21, 22].

In conclusion, we can state the efficacy of NRCT in the absence of correlated peri-operative morbidity. Since there is no evidence to justify a non – operative approach to treating rectal cancer after chemo radiation in complete clinical responders at presents [23]. Surgery remains the standard of care after the neoadjuvant RCT irrespective of the extent of response. Better designed studies are required to clarify some of the issues involved [24]. Improvements in imaging techniques and in the evaluation of biomarkers will allow better patient selection in the hope of the performance of more conservative procedures and application of the “watch and wait” policy.

Authors' Contribution

PR Preparation of the manuscript

FDS Helped in preparation of manuscript.

ER Helped in preparation of manuscript.

MM Helped in preparation of manuscript.

VB Helped in preparation of manuscript.

GP Helped in preparation of manuscript.

MB Helped in preparation of manuscript.

MV Helped in preparation of manuscript.

MR Helped in preparation of manuscript.

GP Concept and design editing of manuscript

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Institute Review Board

Funding

None Declared

Acknowledgement

None

References

[1]. Bonadonna G., Robustelli Della Cuna G., Valagussa P.: Medicina Oncologica, VIII edizione, Milano, Masson, 2007.

[2]. http://www.registri-tumori.it [webgrafia]

[3]. http://www.salute.gov.it/tumori [webgrafia]

[4]. Zolfagari S., Williams L. J., Moloo H., Boushey R. P. : Recatal Cancer: current surgical management, Minerva Chirurgica, 2010; 65(2):197-211. [Pubmed].

[5]. Simunovic M., Smith A. J., Heald R.J: Rectal cancer surgery and regional lymph nodes, Journal of Surgical Oncology, 2009; 99:256–259. [Pubmed].

[6]. Inoue Y., Kusunoki M.: Resection of rectal cancer: a historical review, Surgery Today,2010; 40:501-506. [Pubmed].

[7]. Carlsen E., Schlichting E., Guldvog I. Johnson E., Heald R.J. : Effect of the introduction of total mesorectal excision for the treatment of rectal cancer, British Journal of Surgery 1998; 85:526–529. [Pubmed].

[8]. Påhlman L, Glimelius B: Pre- or postoperative radiotherapy in rectal and rectosigmoid carcinoma. Report from a randomized multicenter trial, Annals of Surgery, 1990; 211(2): 187–195. [Pubmed].

[9]. Bekdash B, Harris S, Broughton CI, Caffarey SM, Marks CG. : Outcome after multiple colorectal tumours, British Journal of Surgery, 1997; 84(10): 1442-1444. [Pubmed].

[10]. Sauer R., Becker H., Hohenberger W. et al.: Preoperative versus Postoperative Chemoradiotherapy for Rectal Cancer, The New England Journal of Medicine, 2004; 351:1731-1740. [Pubmed].

[11]. Fleming FJ, Påhlman L, Monson JR.: Neoadjuvant Therapy in Rectal Cancer, Disease of the Colon and Rectum, 2011; 54(7): 901–912. [Pubmed].

[12]. Kalady MF., de Campos-Lobato LF., Stocchi L. Geisler DP, Dietz D, Lavery IC, Fazio VW. Predictive Factors of Pathologic Complete Response After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation for Rectal Cancer, Annals of Surgery, 2009;250: 582–589. [Pubmed].

[13]. Jakob C, Aust DE, Liebscher B, Baretton GB, Datta K, Muders MH: Lymphangiogenesis in Regional Lymph Nodes Is an Independent Prognostic Marker in Rectal Cancer Patients after Neoadjuvant Treatment, PLoS One. 2011; 6(11). [Pubmed].

[14]. Lidder PG., Hosie KB.: Rectal Cancer : The Role of Radiotherapy, Digestive Surgery, 2005; 22: 41-49. [Pubmed].

[15]. Rivoire M, Malerba M, Gandini A. Rectal cancer margin; Bull Cancer. 2008 Dec;95(12):1177-81. [Pubmed].

[16]. Glynne-Jones R, Mawdsley S, Novell JR. The clinical significance of the circumferential resection margin following preoperative pelvic chemo-radiotherapy in rectal cancer: why we need a common language. Colorectal Dis. 2006 Nov;8(9):800-7. [Pubmed].

[17]. Augestad, Knut M.; Lindsetmo, Rolv-Ole; Stulberg, Jonah; et al. International Preoperative Rectal Cancer Management: Staging, Neoadjuvant Treatment, and Impact of Multidisciplinary Teams WORLD JOURNAL OF SURGERY Volume: 34 Issue: 11 Pages: 2689-2700 DOI: 10.1007/s00268-010-0738-3

[18]. Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Wynn G, Marks J, Kessler H, Gama-Rodrigues J. Complete clinical response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for distal rectal cancer: characterization of clinical and endoscopic findings for standardization. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010 Dec;53(12):1692-8. [Pubmed].

[19]. Glynne-Jones R, Hughes R. Critical appraisal of the 'wait and see' approach in rectal cancer for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation. Br J Surg. 2012 Jul;99(7):897-909. [Pubmed].

[20]. Garcia-Aguila JR., Chen Z, Smith DD, Li W, Madoff RD, Cataldo P, Marcet J, Pastor C: Identification of a Biomarker Profile Associated With Resistance to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy in Rectal Cancer, Annals of Surgery,2011; 254:486–493. [Pubmed].

[21]. Chen Z, Duldulao MP, Li W, Lee W, Kim J, Garcia-Aguilar J. : Molecular Diagnosis of Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer, American College of Surgeons, 2011;212(6) 1008-1017. [Pubmed].

[22]. Toiyama Y, Inoue Y, Saigusa S, Okugawa Y, Yokoe T, Tanaka K, Miki C, Kusunoki M. : Gene Expression Profiles of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Hypoxia-inducible Factor-1 with Special Reference to Local Responsiveness to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy and Disease Recurrence After Rectal Cancer Surgery. Clinical Oncology, 2010; 22:272–280. [Pubmed].

[23]. singh- ranger G, Kumar D. Current Concepts in the Non-Operative Management of Rectal Cancer after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation. Anticancer Research 2011.31: 1795-1800. [Pubmed].

[24]. O’Neill BD, Brown G, Heald RJ, Cunningham RJ, Tait DM. Non-Operative treatment after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2007; 8:625-33. [Pubmed].