Case Report

Solid Pseudopapillary Tumour of Pancreas with a Metachronous Papillary Microcarcinoma of Thyroid

1Walimuni Yohan M Abeysekera, 1Warusha D D de Silva, 2Anusha P Ginige, 1Pragatheswaran Pragatheswaran, 1Rasantha P Kuruppumullage, 1Aruna SK Banagala.

- 1Department of Surgery, Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila, Dehiwala 10350, Sri Lanka.

- 2Department of Pathology, Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila, Dehiwala 10350, Sri Lanka.

- Submitted: April 14, 2012;

- Accepted May 3, 2012,

- Published: May 10, 2012

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction:

Solid pseudo-papillary tumours of the pancreas are uncommon neoplasms of low grade malignant potential usually arising in young females. Association of these tumours with secondary malignancies is exceptionally rare.

Case presentation:

A 14 year old girl detected to have a metachronous papillary microcarcinoma of thyroid, following spleen preserving pancreatectomy for a rare solid pseudo-papillary tumour of the pancreas.

Discussion:

Solid pseudo-papillary tumours of the pancreas are uncommon neoplasms which have a significant female preponderance. Treatment should be mainly surgical since the tumour has a good outcome even in advance stages. Its occurrence with other malignancies is extremely rare.

Introduction

Solid pseudo-papillary tumours of the pancreas are uncommon neoplasms of low grade malignant potential usually arising in young females. Association of these tumours with secondary malignancies is exceptionally rare with only a few cases reported in the world literature. This report discusses the case of a young female presenting with a solid pseudopapillary pancreatic tumour subsequently found to have a papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland. To the best of our understanding, this is an extremely rare occurrence and this is only the second such instance reported in the world literature.

Case report

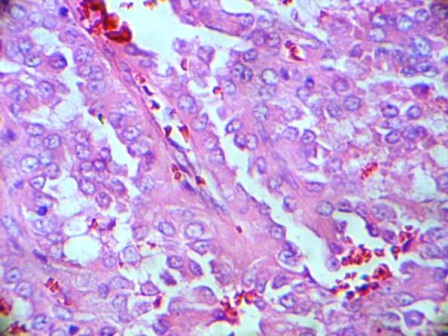

A 14 year old girl presented to the surgical department with a six month history of severe burning epigastric pain associated with vomiting. She had been managed as for ‘gastritis’ but with no response to treatment. A contrast enhanced CT scan was performed and revealed a large 4.8×3.6×3.9 cm size hypo-dense mass in the distal body and tail of the pancreas with enlarged regional lymph nodes (Figure 1). Since the Ultrasound (US) guided Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) was technically difficult due to the location of the pancreatic lesion, surgical resection of the pancreatic body and tail was performed preserving the spleen. Enlarged lymph nodes identified over the tail of the pancreas and along the left gastric vessels were resected with the tumour. Histology confirmed a solid pseudo-papillary tumour of the pancreas. Assessment indicated complete excision of the lesion while all resected lymph nodes (six) in the specimen demonstrated only reactive changes. The patient was referred to the oncologist for further care and was followed up with repeated US of abdomen every 3 months to detect recurrence of the pancreatic tumour. Nearly three and a half years after initial surgery, she was found to have a mild asymptomatic insignificant enlargement of the thyroid gland. An ultrasound scan detected a 10×7×5 mm poorly defined hypo-echoic solid nodule in the right lobe of the thyroid which FNAC revealed as a papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland. Total thyroidectomy performed and the histology confirmed classical papillary microcarcinoma of the right lobe of thyroid in a background of chronic autoimmune thyroiditis (Figure 2).

Figure 1: CT image showing a large hypodense lesion in the pancreatic tail in close apposition to the spleen

Discussion

Since the first description by Frantz in 1959 until the recommendation of the WHO pancreatic work group in 1996, the solid pseudopapillary tumour (SPT) has appeared in the guise of many aliases including Frantz’s tumor, papillary cystic neoplasm, solid and cystic neoplasm and papillary cystic neoplasm [1,2] .

Figure2: Histology of the right lobe of the thyroid demonstrating Papillary Microcarcinoma

It is a rare tumor of low grade malignant potential with an incidence of 0.13% to 2.7% among all pancreatic tumors [3]. There is a marked female preponderance especially in their second and third decade of their life due to reasons yet to be revealed. According to Kosmahl et al SPT may possibly be originating from the genital ridge/ovarian anlage related cells, which are close to pancreatic tissue during embryogenesis and the presence of progesterone receptors in SPTs supports this hypothesis [4] . In another study it was hypothesized that the HBV infection maybe involved in the pathogenesis of SPT due to the presence of the HBV infection in 62.5% patients with SPT [5].

There is conflicting evidence for the common site of SPT in pancreas, some reports suggesting the head and tail [6] but other reports favor the body as well. [7] In our patient it was the body and tail of the pancreas which had the SPT. Clinical presentations of the SPTs are highly nonspecific and occur mainly due to the local pressure on surrounding structures. One Asian study revealed that the most common clinical features as abdominal pain and abdominal discomfort which was the same in our patient. Nearly 20-30% of the SPTs would be incidentally detected during surgery or radiological investigations. [8,9]

Despite its reputation as a low grade malignancy, 3 out of 20 patients will show metastases, commonly to liver, mesentery, omentum, peritoneum and regional lymph nodes [10]. Duodenum, stomach, spleen or major blood vessels are also reported sites of local invasion [9]. In our case we did not identify any evidence of metastasis in imaging studies or during surgery. Peng-Fei Yu et al after an analysis of 553 cases concludes that the clinical factors including sex, age, symptoms, tumor size, location or characteristics were not related to its malignant potential [9]. However, in other reports, the potency of metastasis and the aggressiveness of the SPT was shown to be related to the nuclear polymorphism, mitotic rate, diffuse growth, necrosis and dedifferentiation of the tumor[11]

Diagnosis of SPT would rely mainly on imaging studies such as US, CT or MRI but MRI is superior to CT or USS in detecting the cystic and solid areas of the tumour [9]. FNAC, performed percutaneously or under endoscopic ultrasound guidance may provide histological diagnosis for SPT but the risk of seeding of the needle tract, bleeding, pancreatic fistula and biliary fistula may compromise the procedure [12]. SPT has no specific tumour markers with a diagnostic value[7]. Thus the imaging studies with age and gender should be sufficient to decide surgical intervention [9].

The treatment of choice for SPT should be surgical resection even for a patient with recurrence, local invasion or limited metastasis. The evidence in literature to support a place for chemotherapy or radiotherapy in the treatment for SPT is minimal [9]. Prognosis of SPT is very good even with local recurrence or metastasis with reported 5 year survival rates of greater than 95% [13].

The occurrence of SPT in association with other malignancies has been rarely documented. Gonsalez-Campora and colleagues reported a similar case where a patient with SPT and liver metastases subsequently presented with a papillary thyroid cancer [14]. SPT has also been reported in association with hairy cell leukemia and colon cancer [15]. No definite pathological relationship can be demonstrated between the two tumours and it is possible that this association is at the genetic level or it may be a co-incidence.

Authors’ contribution

WYMA: Designed, prepared and edited the manuscript.

WDDS: supported in Literature review and edited the manuscript.

APG: Supported in providing histology slides & clarified histological data.

PP: Supported in literature review and preparing the manuscript.

RPK: Supported in Histology slide imaging.

ASK: Decision maker on management of the patient, edited the final manuscript

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images.

Acknowledgements

Dr. K.C.K Wasalaarachchi Consultant Histopathology, Colombo South Teaching Hospital.

References

[1]. Frantz V: Tumours of the pancreas: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC 1959.

[2]. Salla C, Chatzipantelis P, Konstantinou P, Karoumpalis I, Pantazopoulou A, Dappola V. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2007; 13: 5158-5163.

[3]. Crawford BE2nd. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas, diagnosis by cytology. South Med J. 1998;91:973-937.

[4]. Kosmahl M, Seada LS, Jänig U, Harms D, Klöppel G. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: Its origin revisited. Virchow Arch. 2000; 436:473–480

[5]. Sun GQ, Chen CQ, Yao JY, Shi HP, He YL, Zhan WH. Diagnosis and treatment of solid pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas: a report of 8 cases with review of domestic literature. Zhonghua Putong Waike Zazhi 2008; 17: 902-907

[6]. Chang H, Gong Y, Xu J, Su Z, Qin C, Zhang Z. Clinical strategy for the management of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: aggressive or less? Int J Med Sci. 2010; 7(5):309-313

[7]. Roberto S, Claudio B, Leonardina F, Massimo F, Stefano C, Giovanni B, Antonietta B, Paola C, Paolo P. Clinical and biological behavior of pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumors: Report on 31 consecutive patients. J Surg Oncol 2007;95:304–310

[8]. Dong DJ, Zhang SZ. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: CT and MRI features of 3 cases. Hepatobilliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006; 5: 300-304.

[9]. Peng-Fei Y, Zhen-Hua H, Xin-Bao W, Jian-Min G, Xiang-Dong C, Yun-Li Z, Qi X. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: A review of 553 cases in Chinese literature World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(10): 1209-1214

[10]. Tang LH, Aydin H, Brennan MF, Klimstra DS. Clinically aggressive solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: a report of two cases with components of undifferentiated carcinoma and a comparative clinicopathologic analysis of 34 conventional cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29: 512-519

[11]. Washington K. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: challenges presented by an unusual pancreatic neoplasm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002; 9: 3-4

[12]. Pettinato G, Di Vizio D, Manivel JC, Pambuccian SE, Somma P, Insabato L. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a neoplasm with distinct and highly characteristic cytological features. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002; 27: 325-334

[13]. Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2005; 200: 965-972

[14]. Gonzalez-Campora R, Rios Martin JJ, Villar Rodriguez JJ, Otal Salaverri C, Hevia Vazquez A, Valladolid JM, et al. Papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas with liver metastasis coexisting with thyroid papillary carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995; 119:268-73.

[15]. Acebo E, Rodilla IG, Torío B, Hernando M, García de Polavieja M, Morales D, Seco I, Bermudez A. Papillary cystic tumor of the pancreas coexisting with hairy cell leukemia. Pathology. 2000; 32(3): 216-219