Original Article

Fibrin sealants, a tool to reduce biliary fistula after laparoscopic exploration of bile duct.

*Belén Martin Arnau, *Manuel Rodriguez Blanco,*Victor Molina Santos, *Berta Gonzalo Prats,*Marina Espinet Blasco, * Antonio Moral Duarte,*Santiago Sánchez Cabús,

- * Department of Surgery, Unit of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery, Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain.

- Submitted: Wednesday, 27 January 2021

- Accepted: Friday, 19 March 2021;

- Published: Wednesday 31 March 2021

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

Abstract

Introduction

The incidence of biliary fistulas after laparoscopic exploration of the main bile duct (LCBDE) for the treatment of choledocholithiasisis

is 5-% after closing the choledochotomy. We evaluate the usefulness of fibrin sealants in reducing the incidence of biliary fistulas.

Material and methods

We present a retrospective analysis of 110 patients diagnosed with choledocholithiasis who underwent LCBDE

between September 2006 and April 2020. The study population was divided into two groups: patients with choledochorrhaphy covered with fibrin sealant adhesive (FS) and patients with uncovered choledochorrhaphy (NSF). We present the analysis of incidence of postoperative biliary fistulas.

Results

89 patients underwent the transcholedochal approach, 19.1% (17/89) choledochorraphy over a Kehr drain (CK) and 80.9% primary choledochorrhaphy (72/89). In the group undergoing closure with primary choledochorrhaphy (PC), 58% (42/72) received fibrin sealant (FS) and 42% (30/72) did not (NFS). In the group undergoing closure over a Kehr drain (CK), 41.2% (7/17) of patients received FS and 58.8% (10/17) NFS.

Analysis of the effect of the sealant in each subgroup found that applying fibrin sealant reduced the incidence of biliary fistulas in the PC group (5% in FS vs 40% in NFS, p 0.0005), but not in the CK group (14.3% in FS vs 10% in NFS, p=1).

Conclusion

Vaporized fibrin adhesive on choledochorrhaphy after primary bile duct closure may play an important role in significantly reducing the incidence of postoperative biliary fistulas.

Keywords

Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration, Choledocholithiasis, fibrin sealant, biliary fistulas, primary choledochorrhaphy.

Introduction

It is considered that approximately 9 to 16% of patients with cholelithiasis can experience concomitant choledocholithiasis [1-3]. However, there is still no consensus on the best therapeutic approach for choledocholithiasis. At present, the two-stage approach with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the preferred option in most centres [4, 5]. Despite this, the results of the endoscopic approach and the laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) and LC in the same procedure are similar in terms of efficacy and associated morbidity [1, 6-16]. One of the reasons why LCBDE has not become the gold standard in the treatment of choledocholithiasis is due to its technical difficulty and the morbidity associated with closure of the choledochotomy after stone removal.

Kehr's T-tube has traditionally been used to decrease the rate of biliary fistulas after choledochorraphy. However, the morbidity associated with the drainage itself and its removal has meant that in recent years this technique has been progressively replaced by bile duct closure using primary Choledochorrhaphy after checking that there is no residual lithiasis with the choledochoscope [17-22]. Nonetheless, the incidence of biliary fistulas after LCBDE varies between 5 and 15% [11, 20, and 22], with this being the main complication associated with the procedure.

In 2014, fibrinogen derivatives with thrombin with tissue-sealant properties appeared on the market, and as a result their use for other purposes has spread. The usefulness of fibrin sealants to reduce biliary fistulas after hepatectomy has been made public [26, 27]. However, there are no human studies that determine the efficacy of biliary sealing to protect choledochorrhaphy after LCBDE.

The objective of this study is to determine the usefulness of fibrin sealant to reduce biliary fistulas after laparoscopic choledochorrhaphy.

Methods

Between September 2006 and April 2020, we carried out 110 consecutive cholecystectomy procedures with laparoscopic exploration of the bile duct in patients with CLT diagnosed via an imaging study.

The data from these patients were collected prospectively in a data base and were analysed retrospectively. The variables analysed were as follows preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative.

Patient selection

Patients were included who had clinical and laboratory signs which were suggestive of CLT ( pain of probable biliary origin and jaundice) which was confirmed with an imaging study, and those with signs of associated cholecystitis were excluded. Radiological diagnosis of CLT was carried out via abdominal ultrasound in 15 patients (13,6%), CT scan in 8patients (7.4%) and MRCP in 87patients (79%).

Informed consent was obtained from all patients after they had been given information about their disease, the up-to-date treatment options and the possibility of conversión to conventional open surgery.

Surgical technique

All patients received antibiotic and antithrombotic prophylaxis in line with the centre’s policy. The supine position was used, allowing the fluoroscopic C-arm to be inserted to carry out the intraoperative cholangiography.

As standard, an intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) was carried out in all patients except those with CLT demonstrated by an imaging study (abdominal ultrasound, CT scan or MRCP) in the 7 days prior to the surgical intervention. If animage suggestive of CLT was observed in the IOC ( filling defect or no passage of contrast to duodenum), a surgical exploration of the bile duct was carried out.

The procedure was carried out using a laparoscopic cholecystectomy technique with the use of 4 trocars (American technique), as previously described. After completely dissecting the triangle of Calot, a small incisión was made in the cystic duct following proximal clipping of the duct to prevent the stones from sliding into the common hepatic duct. A small-diameter (4.5 Fr) cathéter was inserted through the cystic duct to carry out the IOC and to detect any image ssuggestive of CLT oranyanatomical variations, if applicable. If any images minimally suggestiveof CLT were observed, surgical exploration with a choledochoscope was indicated.

Transcystic approach

This approach was used in cases with a large cystic duct which allowed material to be inserted for the removal or for a single CLT of smaller size tan the cysticduct.

After dilating the cystic duct with the laparoscopic dissector, the stones were removed from the main bile duct using a pressure infusión of salin esolution and subsequently, in all cases, with the assistance of a Dormia basket [37] or a balloon catheter (Fogarty®) [38]. After the CLT expulsión manoeuvres, a flexible choledochoscope was used [39] to check that there was no residual choledocholithiasis. The laparoscopic cholecystectomy was then completed in the usual way.

In these patients, given that the main bile duct remained intact, an abdominal drain was not routinely placed.

Choledochotomy approach

This approach was carried out in cases in which the requirements for a transcystic approach were not met (multiple or large-size CLT, small-diameter cystic duct) or if the transcystic approach was unsuccessful.

Exploration of the bile duct was carried out using a longitudinal choledochotomy on the anterior surface measuring around 2 cm in length. The techniques used to remove the stones were lavage with saline solution under pressure to facilitate the removal of small stones and using the Dormia basket and/or balloon catéter tomove the stones towards the abdominal cavity via the choledochotomy orelse towards to duodenum. In all cases, a choledochoscope was sub sequently used in the distal and proximal direction to rule out the presence of residual CLT.

After removal of the CLT, the choledochotomy incisión was closed over a Kehr drain, which was passed progressively, and in accordance with experience, to the primary closure with individual 4/0 braided absorbable sutures, except in cases of acute cholangitis.

In these patients, a Jackson Pratt® no. 13 low-pressure closed-suction abdominal drain was inserted.[40]

Variables analysed

The study population was divided into two groups according to whether they received a fibrin sealant covering the choledochorrhaphy (FS) or not (NFS). The homogeneity of the groups was looked at for the following variables: age, sex, anaesthetic risk (ASA), history of abdominal surgery, conversion to open surgery, method of stone removal. The incidence of postoperative biliary fistulas in both groups was analysed. Bile leakage was defined as persistent bile drainage of more than 50 ml/day for more than 3 days

[36]. The sample was then stratified into two subgroups according to which technique for choledochotomy closure was used: choledochorrhaphy with a Kehr's drain (CK) or primary choledochorrhaphy (PC). The incidence of biliary fistulas was analysed in each subgroup according to whether they belonged to the FS or NFS group. Complications for each group were compiled according to the Dindo-Clavien classification [29]

[30], average hospital stay duration and need for reintervention.

Statistics Analysis

The continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test orthe Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. The chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables. P <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Unless specifically stated otherwise, the data are shown as a mean ± standard deviation.

The statistical analysis was carried out using commercially available SPSS para Windows versión 23.

Results

Between September 2006 and April 2020, we carried out 110 laparoscopic cholecystectomies with exploration of the bile duct (LCBDE) due to lithiasis at our centre.

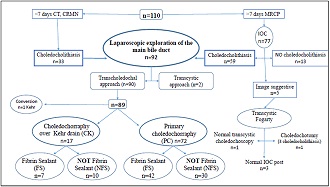

77 patients (70%) had diagnostic radiology studies for choledocholithiasis carried out more than 7 days before the intervention. These patients underwent an intraoperative cholangiography (IOC), the result of which showed no choledocholithiasis in 13/77 patients (16.8 %) and clear presence of choledocholithiasis in 59/77 patients (76.6%). In the remaining 5/77 cases (6.5%), normal bile-duct morphology was observed up to the outlet, but with no signs of passage of contrast to the duodenum. In these cases, pressure infusion of saline solution was carried out, with subsequent insertion of a balloon catheter through the transcystic route. In 3 cases (4.16%), no stone release was observed and the subsequent IOC was carried out normally. In 1 patient (1.3%), a transcysticcholedochoscopy was able to be carried out, which ruled out the presence of residual stones. In the 5th case, there was a striking but somewhat unclear image of choledocholithiasis, and a choledochotomy to remove 3 stones and subsequent choledochoscopy to correctly confirm it were carried out (Fgure 1).

Figure1. Outline of results.

In the patients with confirmed choledocholithiasis, the exploration of the bile duct was carried out using the transcystic approach in 2 patients (2.2%) and the transcholedochal approach in 97.8% (90/92). The choledocholithiasis was satisfactorily resolved in all patients undergoing the transcystic approach, while 4 patients (4.3%) who underwent the transcholedochal approach had residual choledocholithiasis. Primary closure of the choledochotomy was carried out in 80.9% (72/89), with choledochorraphy over a Kehr drain in 19.1% (17/89) of patients. The patients with a Kehr drain maintained this in situ for 26.3±23.7 days before it was removed.

All procedures were carried out using laparoscopy except one case (0.9%) in which conversion to open surgery was carried out due to difficulties removing the choledocholithiasis. There were no statistically significant differences in the conversion rate according to the approach (0.9% vs 0%, p: 0.98).

During the study period, 89 patients underwent the transcholedochal approach, 19.1% (17/89) choledochorraphy over a Kehr drain (CK) and 80.9% primary choledochorrhaphy (72/89). In the group undergoing closure with primary choledochorrhaphy (PC), 58% (42/72) received fibrin sealant (FS) and 42% (30/72) did not (NFS). In the group undergoing closure over a Kehr drain (CK), 41.2% (7/17) of patients received FS and 58.8% (10/17) NFS.

The mean surgical time was 142±36.7 minutes, with the transcystic route being 170±14.1 minutes and the transcholedochal route being 141±36.9 minutes (p= 0.28). The mean postoperative stay duration was 6.5±7.3 days, being longer for the group undergoing the transcholedochal approach (6.7±7.6 days) than for the transcystic approach (2 days (SD:0)) although without differences p=0.38. The postoperative stay duration for the group which developed biliary fistulas was 11.6±15.2 compared to the group that did not develop it (6.0±3.8), which is statistically significant p 0.006.

Biliary complications

16 patients (17.7%) experienced a biliary fistula which persisted for 19±17.3 days

[41].

The incidence of biliary fistula in our series was 2.3% (2/89) in the group with a Kehr in situ, one of them from the FS group and the other from the NFS group. In the PC group, the incidence of fistula overall was 15.7% (14/89), 4.7% (2/42) of those with FS and 40% (12/30) of those with NFS. Analysis of the effect of the sealant in each subgroup found that applying fibrin sealant reduced the incidence of biliary fistulas in the PC group (5% in FS vs 40% in NFS, p 0.0005), but not in the CK group (14.3% in FS vs 10% in NFS, p=1) (Table 1and 2).

| Biliary Fistula |

YES |

NOT |

TOTAL |

FibrinSealant

YES |

3 |

46 |

49 |

FibrinSealant

NOT |

13 |

27 |

40 |

| TOTAL |

16/89 (18%) |

73/89 (82%) |

89 |

| Biliary Fistula |

YES |

NOT |

TOTAL |

KehrDrain

YES |

2 |

15 |

17 |

KehrDrain

NOT |

14 |

58 |

72 |

| TOTAL |

16/89 (18%) |

73/89 (82%) |

89 |

Test Fisher P= 0.7268

In the PC group, fibrin sealant proved to be a protective factor, with an odds ratio of 4.75 CI (1.3-17.35).

Regarding the treatment of fistulas, conservative management was carried out in 14 patients with the drain remaining in situ until resolved. 2 patients with biliary fistulas required specific treatment; one required reintervention for surgical drainage of the biloma and the other required insertion of a percutaneous drain. Neither of these cases had a T-tube in situ. The medical complications are summarised in (Table 3and 4). A total of 6 patients experienced medical complications in the form of pneumonia, urinary-tract infection and postoperative adynamic ileus, which progressed well with medical treatment. None of the patients showed clinical, laboratory or radiological signs of biliary stricture in the long-term postoperative follow-up.

| Complications |

n |

% |

| Biliary fistula |

16 |

14.5 |

| Residual choledocholithiasis |

4 |

3.6 |

| Bleeding |

3 |

2.7 |

| Residual collection |

3 |

2.7 |

| Coledocian stenosis |

0 |

0 |

| Paralytic ileus |

1 |

0.9 |

| Pneumonia |

2 |

1.8 |

| Urinary infection |

3 |

2.7 |

| Postoperative complication Clavien Dindo |

n |

% |

| Minor |

21 |

19.1% |

| I |

17 |

15.4 |

| II |

4 |

3.6 |

| Major |

8 |

7.3% |

| IIIa |

5 |

4.5 |

| IIIb |

1 |

0.9 |

| IV |

0 |

0 |

| V |

2 |

1.8 |

The overall mortality for the series was 1.8% (2/110), secondary to bleeding complications. Overall, 3 patients (2.7%) experienced postoperative bleeding, with 2 cases requiring reintervention: one patient experienced liver cirrhosis which had not been previously diagnosed, presenting with decompensation and subsequent multiple organ failure following bleeding of the cystic artery, eventually resulting in death; another patient experienced a hypovolemic shock secondary to a pseudoaneurysm of the gastroduodenal artery, eventually resulting in death despite emergency reintervention; the third case of bleeding corresponded to a haematoma in the surgical bed, which was treated conservatively.

Discussion

At present, LCBDE is considered to be an equally effective method for treating choledocholithiasis as ERCP and subsequent laparoscopic cholecystectomy, since they share a similar complication rate. Therefore no approach has demonstrated superiority over another in terms of effectiveness [1, 13-16]. Despite this, in most hospitals the endoscopic approach is chosen to treat patients with bile duct stones, a fact reflected in a national North American survey that showed that 86% of surgeons chose to carry out an ERCP and a subsequent LC to treat choledocholithiasis5. The most important reasons for the preference for a two-stage procedure are the availability of expert endoscopists, having no choledochoscopy in many institutions or being unfamiliar with it, and in particular the lack of LCBDE technique experience.

The difficulty of performing a hermetic closure of the bile duct by laparoscopy without causing a stricture is one of the greatest difficulties faced by surgeons who choose this approach. Despite the fact that not using the Kehr tube has brought advantages by reducing the morbidity of LCBDE[17, 20, 31], the incidence of biliary fistulas after choledochotomy and laparoscopic choledochorraphy is still seen in 5 to 15% of patients [20]. Our study is consistent with these data, with overall figures for biliary fistula of 17.7%. Four of our patients developed a type C fistula requiring reintervention, 3 of them resulting in death, but most cases of type B fistula were resolved without the need for therapeutic intervention. In order to reduce the rate of biliary fistula, several surgical strategies have been developed; one of them is choledochorrhaphy protected by transpapillary [19, 32] or transcholedochal prosthesis, arguing that the pressure reduction in the main bile duct achieved by keeping the papilla open with the stent should reduce bile filtration through the choledochal suture. However, some series show that the prosthesis itself can be a cause of morbidity, in addition to the discomfort caused to the patient by the need for an endoscopy to remove it if it is not removed spontaneously or if the Kehr requires manual removal.

The use of fibrin sealants as haemostatic agents has been known about since the 1990s [33], and since then their use has been widespread to achieve haemostasis of solid organs with diffuse bleeding [24, 25]. At the same time, it has been proven that the combination of fibrinogen and thrombin assists tissue sealing, enabling the sealing of sutures in vascular surgery and in the gastrointestinal tract [23]. The combination of the haemostatic effect and biliary sealing began to be considered of special interest in liver surgery [27, 34]. Although there are studies that reveal the fibrinolytic capacity of bile

in vitro, theoretically affecting the integrity of the fibrin-collagen sheets[35], Toti

et al. have recently published the results of a study that demonstrates the reduction of biliary fistulas following split liver transplant in adults using a fibrin-collagen sponge [26]. Although the biliary sealing effect should be just as effective after choledochorrhaphy in LCBDE, only studies in animals have shown good results for this indication. There are no published experiments in humans.

In our centre, fibrin sealant began to be used in 2010 to protect choledochorrhaphy from biliary fistulas. Our results show that applying the sealant halved the number of fistulas in the overall series, although only at the expense of patients who did not have a Kehr drain.

In the absence of biliary hyperpressure through the Kehr drain, adding sealants to choledochorrhaphy is of no benefit. By contrast, after a primary choledochorrhaphy, this increase in biliary pressure with the papilla closed seems to be better supported with the application of fibrin sealants, significantly reducing biliary fistulas. It is evident that, given the same results in terms of fistulas occurring, primary closure of the common bile duct offers advantages over closure protected by prosthesis, given the morbidity of stents and their removal.

Furthermore, the increased costs from using fibrin sealants could be offset by a reduction in overall hospital stay duration as a consequence of lower morbidity. Although our study has the bias of being a retrospective study in which the use of the sealant adhesive and the type of choledochorrhaphy has not been documented, it is a study that describes the beneficial sealing effect of fibrin used in the bile duct.

Conclusion

As we wait for randomised clinical trials with a larger sample size that could add stronger evidence, we believe that the most advisable choledochotomy closure technique after LCBDE should be primary choledochorrhaphy protected with vaporized fibrin sealant.

Authors' contributions

BMA: Conceived and designed the study, performed the analysis and prepared the manuscript.

MRB: Prepared the manuscript

VMS: Conceived and designed and helped with the analysis of the data.

BJP: Conceived and designed and helped with the analysis of the data.

MEB: Data collection and analysis

AMD: Analysis and interpretation of data

SSC: Data analysis, interpretation and preparation of manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Statement of Ethics and consent

The study was approved by the Institute Ethics committee and informed consent

was taken from all patients

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

References

[1]. Martin DJ, Vernon DR, Toouli J. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006. CD003327. [PubMed]

[2]. Vezakis A, Davides D, Ammori BJ, Martin IG, Larvin M, McMahon MJ. Intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. SurgEndosc. 2000; 14:1118–22. [PubMed]

[3]. Velanovich V, Morton JM, McDonald M, Orlando R 3rd, Maupin G, Traverso LW, et al. Analysisofthe SAGES outcomesinitiativecholecystectomyregistry. SurgEndosc. 2006; 20:43–50. [PubMed]

[4]. Stromberg C, Nilsson M. Nationwide study of the treatment of common bile duct stones in Sweden between 1965 and 2009. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1766–74. [PubMed]

[5]. Baucom RB, Feurer ID, Shelton JS, Kummerow K, Holzman MD, Poulose BK. Surgeons, ERCP and laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: Do we need a standard approach for common bile duct stones? SurgEndosc. 2016;30:414–23. [PubMed]

[6]. Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Horn JK, Siperstein AE, Schecter WP, Campbell AR, et al. Prospective randomized trial of LC+LCBDE vs ERCP/S+LC for common bile duct stone disease. Arch Surg. 2010;145:28–33. [PubMed]

[7]. Noble H, Tranter S, Chesworth T, Norton S, Thompson M. A randomized, clinical trial to compare endoscopic sphincterotomy and subsequent laparoscopic cholecystectomy with primary laparoscopic bile duct exploration during cholecystectomy in higher risk patients with choledocholithiasis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:713–20[PubMed]

[8]. Sgourakis G, Karaliotas K. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and cholecystectomy versus endoscopic stone extraction and laparoscopic cholecystectomy for choledocholithiasis. A prospective randomized study. Minerva Chir. 2002;57:467–74 [PubMed]

[9]. Cuschieri A, Lezoche E, Morino M, Croce E, Lacy A, Toouli J, et al. E.A.E.S. multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing two-stage vs single-stage management of patients with gallstone disease and ductal calculi. SurgEndosc. 1999;13:952–7. [PubMed]

[10]. Rhodes M, Sussman L, Cohen L, Lewis MP. Randomised trial of laparoscopic exploration of common bile duct versus postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for common bile duct stones. Lancet. 1998;351:159–61.[PubMed]

[11]. Bansal VK, Misra MC, Rajan K, Kilambi R, Kumar S, Krishna A, et al. Single-stage laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and cholecystectomy versus two-stage endoscopic stone extraction followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones: a randomized controlled trial. SurgEndosc. 2014; 28:875–85. [PubMed]

[12]. Ding G, Cai W, Qin M. Single-stage vs. two-stage management for concomitant gallstones and common bile duct stones: A prospective randomized trial with long-term follow-up. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:947–51. [PubMed]

[13]. Dasari BV, Tan CJ, Gurusamy KS, Martin DJ, Kirk G, McKie L, et al. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9. CD003327.

[14]. Clayton ES, Connor S, Alexakis N, Leandros E. Meta-analysis of endoscopy and surgery versus surgery alone for common bile duct stones with the gallbladder in situ. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1185–91. [PubMed]

[15]. Tranter SE, Thompson MH. Comparison of endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct. Br J Surg. 2002;;89:504–1495. [PubMed]

[16]. Liu JG, Wang YJ, Shu GM, Lou C, Zhang J, Du Z. Laparoscopic versus endoscopic management of choledocholithiasis in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta- analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014; 24:287–94. [PubMed]

[17]. Martinez-Baena D, Parra-Membrives P, Diaz-Gomez D, Lorente-Herce JM. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and antegrade biliary stenting: Leaving behind the Kehr tube. Rev EspEnferm Dig. 2013; 105:125–9. [PubMed]

[18]. Jameel M, Darmas B, Baker AL. Trend towards primary closure following laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90:29–35. [PubMed][PMC Full Text]

[19]. Isla AM, Griniatsos J, Karvounis E, Arbuckle JD. Advantages of laparoscopic stented choledochorrhaphy over T-tube placement. Br J Surg. 2004;91:862–6. [PubMed]

[20]. Podda M, Polignano FM, Luhmann A, Wilson MS, Kulli C, Tait IS. Systematic review with meta-analysis of studies comparing primary duct closure and T-tube drainage after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration for choledocholithiasis. SurgEndosc. 2016;30:845–61. [PubMed]

[21]. Shojaiefard A, Esmaeilzadeh M, Ghafouri A, Mehrabi A. Various techniques for the surgical treatment of common bile duct stones: A meta review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009;2009:840208. [PubMed] [PMC Full Text]

[22]. Wen SQ, Hu QH, Wan M, Tai S, Xie

XY, Wu Q, et al. Appropriate patient selection is essential for the success of

primary closure after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Dig Dis Sci.

2017;62:1321–6. [PubMed]

[23]. Rickenbacher A, Breitenstein S,

Lesurtel M, Frilling A. Efficacy of TachoSil a fibrin-based haemostat in

different fields of surgery — a systematic review. Expert OpinBiolTher.

2009;9:897–907. [PubMed]

[24]. De Boer MT, Boonstra EA, Lisman T, Porte RJ. Role of fibrin sealants in liver surgery. Dig Surg. 2012; 29:54–61[PubMed]

[25]. Hanna EM, Martinie JB, Swan RZ, Iannitti DA. Fibrin sealants and topical agents in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: A critical appraisal. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014; 399:825–35. [PubMed]

[26]. Toti L, Attia M, Manzia TM, Lenci I, Gunson B, Buckels JA, et al. Reduction in bile leaks following adult split liver transplant using a fibrin-collagen sponge: A pilot study. Dig Liver Dis. 2010; 42:205–9.

[PubMed]

[27]. Simo KA, Hanna EM, Imagawa DK, Iannitti DA. Hemostatic agents in hepatobiliary and pancreas surgery: A review of the literature and critical evaluation of a novel carrier- bound fibrin sealant (TachoSil). ISRN Surg. 2012;2012:729086[PubMed][PMC Full Text]

[28]. Koch M, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Rahbari NN, Adam R, Capussotti L, et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: A definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery. Surgery. 2011; 149:680–8. [PubMed]

[29]. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13 [PubMed][PMC Full Text]

[30]. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: Five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–96. [PubMed]

[31]. El-Geidie AA. Is the use of T-tube necessary after laparoscopic choledochotomy? J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:844–8. [PubMed]

[32]. Tang CN, Tai CK, Ha JP, Tsui KK, Wong DC, Li MK. Antegrade biliary stenting versus T-tube drainage after laparoscopic choledochotomy—a comparative cohort study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:330–4 [PubMed]

[33]. Martis G, Miko I, Szendroi T, Kathy S, Kovacs J, Hajdu Z. Results with collagen fleece coated with fibrin glue (TachoComb). A macroscopical and histological experimental study. Acta Chir Hung. 1997;36:221–2. [PubMed]

[34]. Berrevoet F, de Hemptinne B. Use of topical hemostatic agents during liver resection. Dig Surg. 2007;24:288–93.[PubMed]

[35]. Boonstra EA, Adelmeijer J, Verkade HJ, de Boer MT, Porte RJ, Lisman T. Fibrinolytic proteins in human bile accelerate lysis of plasma clots and induce breakdown of fibrin sealants. Ann Surg. 2012;256:306–12 [PubMed]

[36]. Conrad C, Wakabayashi G, Asbun HJ, Dallemagne B, Demartines N, Diana M, et al. IRCAD recommendation on safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017 Nov; 24(11):603-615 [PubMed]

[37]. Hamouda AH, Goh W, Mahmud S, Khan M, Nassar AH. Intraoperative cholangiography facilitates simple transcystic clearance of ductal stones in units without expertise for laparoscopic bile duct surgery.SurgEndosc. 2007 Jun; 21(6):955-9. [PubMed]

[38]. Mourad FH, Khalifeh M, Khoury G, Al-Kutoubi A.Common bile duct obstruction secondary to a balloon separated from a Fogarty vascular embolectomy catheter during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. SurgEndosc. 2000 May; 14(5):500-1[PubMed]

[39]. Ahmed T, Alam MT, Ahmed SU, Jahan M.Role of intraoperative flexible Choledochoscopy in calculous biliary tract disease.Mymensingh Med J. 2012 Jul; 21(3):462-8. [PubMed]

[40]. Darwin P, Goldberg E, Uradomo L. Jackson Pratt drain fluid-to-serum bilirubin concentration ratio for the diagnosis of bile leaks. GastrointestEndosc. 2010 Jan; 71(1):99-104. [PubMed]

[41]Koch M, Garden OJ, Padbury R, Rahbari NN, Adam R, Capussotti L, et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery. Surgery. 2011 May;149(5):680-8 [PubMed]